When Patrick Foley signed up to be a single foster parent in Washington D.C. in 2009, he did so as an openly gay single man. That meant he was often the first person Child Family Services (CFS) would call when they needed to find an accepting home for a queer foster kid in D.C.

“I was recruited by CFS as a foster parent, specifically to house gay teenagers,” Patrick said. “When I started 12 years ago, they were having real problems getting foster homes for gay teens.”

It was obvious to Patrick what was happening at the time; not only were scores of teens coming out and being stigmatized and rejected by their own families, they were also at risk of being shunned by foster parents who were meant to offer any child a safe home.

“Once they came out, the foster parents were reluctant to have them in the house,” Patrick explained. “Some of the guys who came to me were not even allowed to talk about being gay in foster homes, or they could not have friends over. They couldn’t date, which was just bizarre to me. That’s why CFS wanted to find ‘gay homes’ that would be accepting, and really a good influence on these kids.”

Gay adults are often no strangers to forming a ‘found family’ of their own. Those who become licensed foster parents join a long line of gay parental figures who have provided queer foster youth an important safe haven over the years. And there are plenty of queer kids in need of a loving home; it’s estimated that as many as 30 percent of foster youth in the U.S. identify as LGBTQ+, according to the Human Rights Campaign.

Sadly, discrimination in foster care continues to be pervasive, making it difficult for gay parents in many states to offer homes to the kids who need one. Progress has definitely been made since Patrick was first licensed as a foster parent, but in interviews with several queer foster dads and youth, it’s clear we still have much further to go.

Why Queer Parents Are Essential to the Foster Care System

Gay foster parents like Patrick have long been a necessity within the U.S. foster care system. Up until recent years, social workers would turn to openly gay foster parents as sanctuaries for queer youth who had been rejected by their biological families because of their sexuality.

In fact, it was only about a decade ago that foster parents were legally also allowed to refuse to take in a child because they identified as LGBTQ+. (Though it should be noted that openly queer kids still face plenty of discrimination in many ways, both legally and otherwise, then and now.)

Interested in becoming a foster dad? Visit GWK Academy

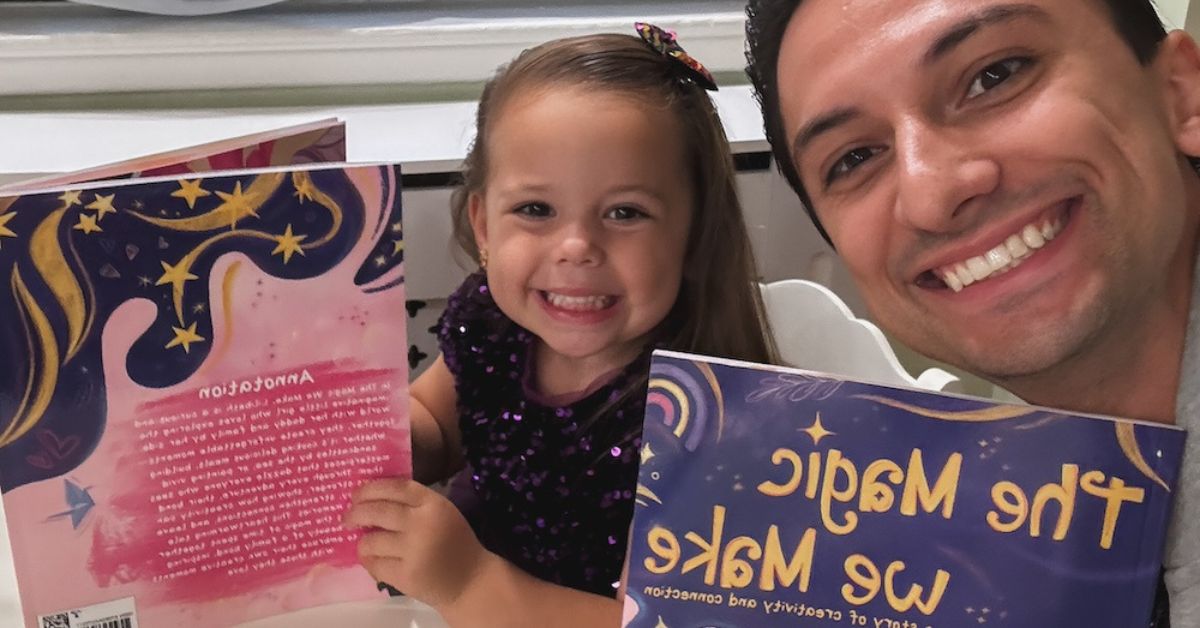

Patrick welcomed his first gay foster teen, 16-year-old Rashard, in early 2010. Although Rashard had been turned away from his family home and placed with Patrick because he was gay, Patrick said he didn’t think much about Rashard’s sexuality at all.

“A gay teenager is the same as a straight teenager as far as their major problems, which would be school, planning for the future, all the regular teenage stuff they go through,” Patrick laughed.

“I think the fact that I was gay was easier for him to adjust,” he continued. “As a young Black teenager, at the time Rashard had less in common with me than he would have normally. So since I was gay, it was easier for him to be himself. He could do what he wanted as part of his growing process. It was probably easier for him than it was for me, because I still had to deal with a teenager!”

In 2012, Patrick took in a second gay Black foster teen; 16-year-old Eric. The following summer 16-year-old Emmanuel joined their home. In 2014, Isaiah was the fourth gay foster youth to be placed in Patrick’s home, and in 2017, Patrick took in Western, who arrived right before his 15th birthday.

Patrick says his five sons are all individual characters, and are very different from each other. After they were placed in his queer-affirming foster home, he said the five young men started becoming noticeably more comfortable in themselves, and they quickly bonded like family.

“It was fun,” he said. “They were just like brothers. Some days they loved each other, some days they hated each other. That’s what it was like in my house growing up too! It was good. And they all watch out for each other, which is really nice.”

Because some of his son’s biological parents wouldn’t give up their rights, Patrick was unable to adopt each boy until he turned 18. Since there was such an age gap between the oldest and youngest, and he didn’t want there to be “two levels” in his family, Patrick waited until all his sons were adults before he adopted all five of them together. Their mass adoption day was June 22nd, 2021, all of which was virtual. Patrick was given a family ring when he was young, and he made copies for each of his sons to mark the occasion.

“We had a dinner to celebrate, but it was almost anti-climactic because we’d been working up to it for years,” he said. “It was just the official part. But it was a really nice feeling.”

Progress for LGBTQ Foster Youth – But A Long Road Ahead

Patrick is now one of the co-trainers for foster parent licensees in D.C. These days, he said D.C.’s CFS does not recruit specifically for gay foster parents, because all foster parents in the District are now taught that they must be open to the possibility of taking in a foster kid who ends up identifying as LGBTQ+. If they’re not, Patrick said they are encouraged to disclose their stance at the beginning of their licensing process, so they can be considered unsuitable for the role.

While several states have updated their policies to curb the negative treatment of gay teens in foster care, others sadly have not. According to Movement Advancement Project, there are currently 18 U.S. states and four territories with no explicit protections against discrimination in foster care based on sexual orientation or gender identity.

Even in states that do mandate inclusive training and policies in the foster system, homophobia still persists, from biological families and foster homes to foster care workers.

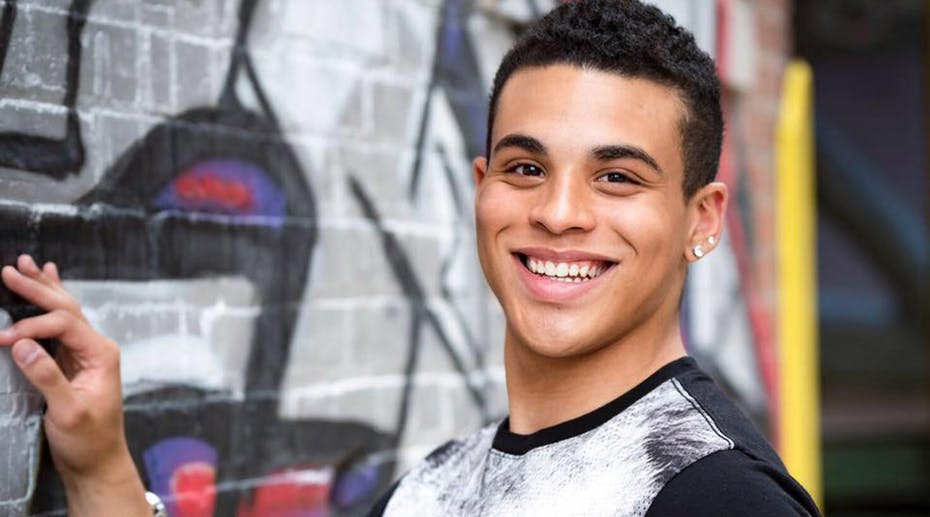

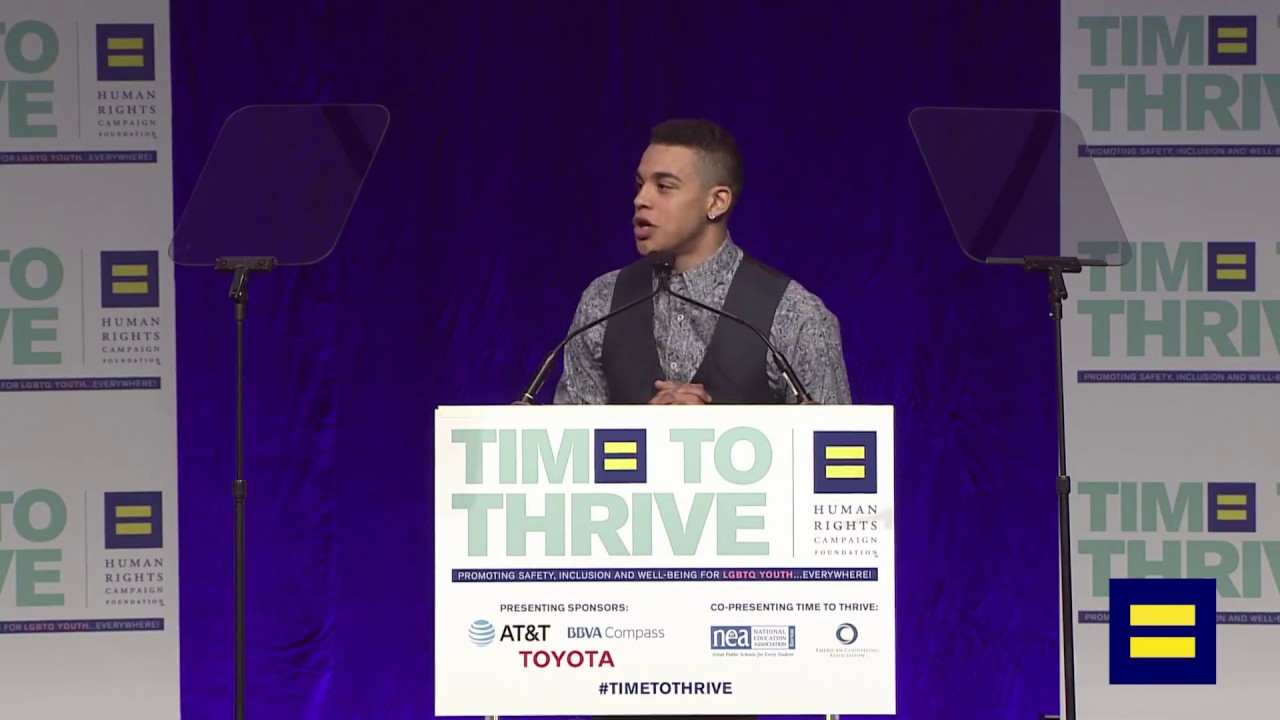

Former foster youth Weston Charles-Gallo — who is now an advocate with the group FosterClub, which advocates for young people with experience in foster care — was 14 years old when he was told to leave his father’s house in Kansas because he was gay. Then, in 2014, a social worker told Weston that several potential families didn’t want him placed with them because they thought he could “turn the other children gay, or be a predator.”

At 21-years-old, Weston told the U.S. Congress Ways and Means Committee how he faced truly awful homophobia within the U.S. foster care system. He also explained how thankful he was to be fostered by two gay dads. In fact, being placed in a home with same-sex parents was an important and affirming experience for Weston.

“When I was 15, I received the amazing news that my impermanence in foster care was a thing in the past,” Weston told members of Congress in May 2021. “I was placed with my two dads, and six siblings. My dads showed me what it was like to witness a true marriage and live a normal life, expressing the meaning of family.”

As a gay teenager, Weston found it to be a life-altering experience once he was accepted into a family with same-sex parents. Not only was he allowed to be his authentic self, he could also look to his dads as an example of a loving relationship between two men who had kids.

“Before I lived with them, I never pictured myself marrying someone, or even having a family,” Weston said. “But they proved to me that anything is possible, and without them in my life constantly supporting and encouraging me, I don’t know where I would be or even if I would be alive today. I finally found a home where I can live my authentic self.”

The federal government doesn’t currently require child welfare agencies to collect information about children’s sexual orientation or gender identity, but according to a 2019 study, teens in foster care are three times more likely to identify as LGBTQ+ than youth not in foster care. Experts believe a large portion of queer-identifying youth are likely in the system because they have been rejected by their families due to how they identify.

Many child welfare agencies continue to place LGBTQ+ foster teens with openly LGBTQ+ foster parents with no problem. But in much of the South and the Midwest, queer teens are less likely to be placed with same-sex parents, because LGBTQ+ adults also face discrimination in the foster system.

According to MAP, 11 states, including Kansas, South Carolina, Mississippi, Tennessee, the Dakotas, and Virginia, have passed laws permitting state-licensed child welfare agencies to “refuse to place and provide services to children and families, including LGBTQ people and same-sex couples, if doing so conflicts with their religious beliefs.”

Interested in becoming a foster dad? Visit GWK Academy

A long history of queer dads fostering queer youth

As is often the case, the laws around family issues like fostering and guardianship are slow to catch up to the way society already works. For generations before gay men like Weston’s dads and Patrick were legally fostering queer teens, gay men were caring for gay teens who had no other place to go, rather than letting them enter the foster system or become homeless.

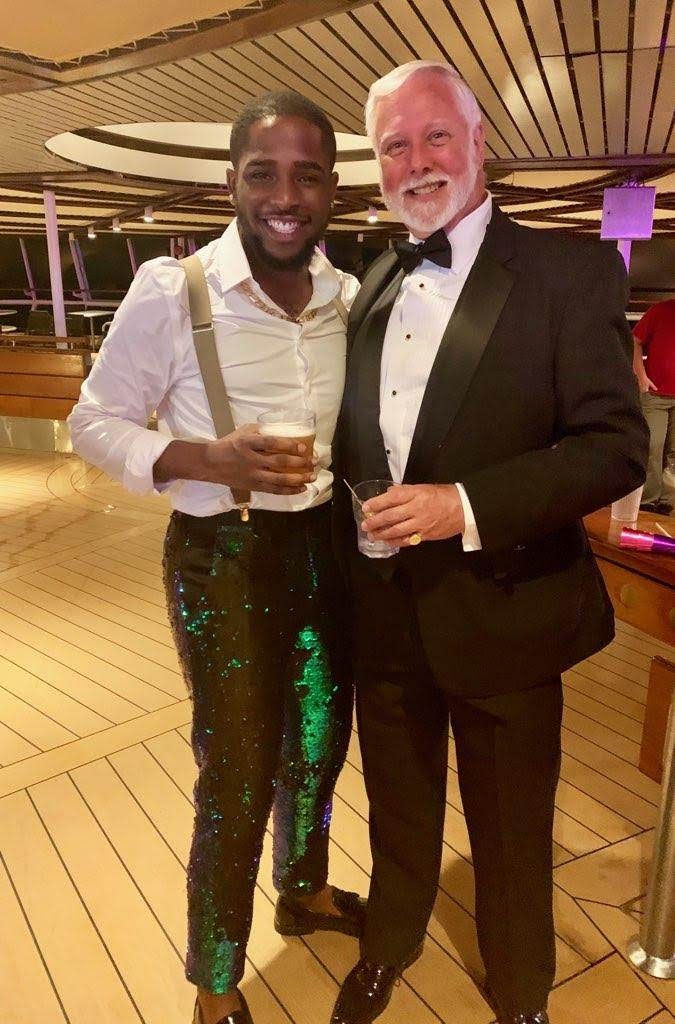

Dr. Marshall Forstein, an Associate Professor of Psychiatry at Harvard, and his late husband Lawrence “Khari” Farrell, a former social worker and psychologist, were the first openly-gay couple to adopt a baby in Massachusetts in 1986. The boy’s parents had died, and the couple took him in as a newborn.

Five years later, Dr. Forstein met 15-year-old Randy, who also needed a home, but for a very different reason; Randy was gay, and had faced abuse at home.

“It wasn’t a formal [foster care] placement,” Marshall explained. “He had come to a seminar I was teaching on gay and lesbian teens being raised by straight parents, and he was on the panel. At the end of the day, [we learned] that he had just finished a program for gay teens, and they needed the bedroom for somebody new. So he was just going to go to a shelter. I was stunned.”

Recalling his own coming out experience, and how accepting his own parents had been, Marshall decided he couldn’t let a gay teen face that kind of rejection simply for being himself. He immediately called his husband, and the couple agreed to take Randy into their home, initially just for a few nights, until he could figure out his next steps.

But it became clear there was no option for Randy but to enter foster care. And of course, back in 1991, that essentially meant he would be thrown into a whole new population, which included more parental figures that could reject him because of his sexuality. Khari and Marshall decided to sit down with their 5-year-old son, and asked what he thought about Randy joining their family for good.

“I’ll never forget it,” Marshall smiled, recalling his young son’s words. “He got very quiet, he scrunched up his nose, looked at us, and said ‘When my mom and dad died, you made me a family. So we need to make Randy a family too.’”

Since Randy’s mother wouldn’t give up her parental rights, the couple instead became his “informal” foster parents. As a gay couple raising a gay teenager in the early 1990s, their situation came with a lot of social stigma. Especially, Marshall explained, from the gay community.

“We [took Randy in] mostly because of his history of being sexually abused, and interestingly enough the comments about taking in a teenager came more from the gay community than from the straight community,” Marshall remembered. “Some of the viciousness of gay men who would make comments, like ‘Oh, so you have a house-boy now?’ and ‘Is he sleeping in the same bed with you two?’ It was horrible. As if gay men have no boundaries or parental instincts. That was so disconcerting to us.”

As some of the only openly-gay men with kids at the time, Marshall said he felt like some of those malicious words may have been due to jealousy from men who simply couldn’t see themselves being fathers. Now more than three decades on, he said he is glad to see gay men normalizing being dads, and that gay dads generally face less stigma from their own community.

It may have had its ups and downs, but Marshall said fostering a young member of the gay community was an important move for his family. After Khari passed away nearly four years ago, Marshall was supported by the love and strength of his sons. For other gay men open to fostering gay teens, Marshall said it is a truly life-changing experience for all involved.

“We were in a good place to do something, and we learned more than we ever imagined,” Marshall explained. “And, as gay men, it gave us a purpose in life that would be different from what we were told it would be.”

***

It’s evident that queer foster parents and queer foster youth have always been around, and will continue to be. Gay dads who are open to fostering queer youth are undeniably essential to the system, not just because they offer caring, qualified homes to kids in need, but because they can also offer an important safe haven for the disproportionate number of queer youth currently in the system.

LGBTQ foster youth, in particular, make clear the need for more LGBTQ foster parents in the system. “As a queer former foster youth, something that really caused me a lot of fear and anxiety was my LGBTQ+ identity and how it would impact those I lived with and their reactions to my identity,” said Rebo Olson (pictured below), a youth leader with FosterClub. “Having more openly LGBTQ+ foster parents is crucial because there are some things that people can’t understand or know about unless they’re a part of the community.”

Unfortunately, the discrimination within the U.S. foster system will likely continue until the nation has meaningful action at the federal level. There are two pieces of current legislation that could make real waves; the Equality Act, which would provide explicit anti-discrimination protections for LGBTQ+ people across several key areas of life, including employment, housing, credit, education, public spaces, and services, federally funded programs, and jury service. And the John Lewis Every Child Deserves a Family Act, which would prohibit federally-funded child welfare service providers from discriminating against children, families, and individuals based on their religion, sex, sexual orientation, gender identity, or marital status. The Every Child Act would also ensure that children and youth in foster care receive the identity-affirming, culturally competent care they deserve.

Reach out to advocacy groups like FosterClub and Family Equality to join the fight.