Somewhere deep in the jungle of Facebook groups for would-be parents, I posted my shot in the dark. Here’s what I actually wrote in early 2015:

Hello to all and thanks for the add!

My partner and I are potential IPs [Intended Parents] in the information-gathering stage. We live in Austin where I manage a real estate firm and he’s a nurse. I think the goal right now is to casually make connections while we make decisions on gestational vs traditional, indy vs. agency. I hope it’s ok if we just kind of hang back and learn from you guys for the time being! Talk soon!

I spent half an hour agonizing over just the right placement of exclamation points to help me sound easy-going and well-adjusted. Now, if I were being candid, here’s how it should’ve read:

Hello to all and thanks for the add!

I’m here to tell you about a huge hole in my life that I’ve tried desperately for a decade to fill with work, travel and volunteering! It’s not that I don’t know what’s missing. I’ve known since I was a little boy that I wanted a family, and for years have said we’d try “someday.” But really I’m paralyzed by the fear that if I take steps to make it happen, something will go wrong and I will be worse off for trying. I will have acknowledged that my dream for my life, the thing I silently pray for at night, is to become a father. So if I try and it doesn’t work out, I’ve admitted to myself and everyone else that my life was unfulfilled. I’m fairly certain that my partner feels the same, although I’ve actually never asked him for fear that together we’ll set our hearts on becoming fathers only to fail miserably and wind up in a deeper emotional chasm than when we started. Obviously, this is a cry for help. Talk soon!”

Two and a half years later, I can poke fun at myself for that tentative, guarded attempt at connection because right now, across the room, I am watching silently as my husband Shannon makes funny faces at our three month-old son Jake until he squeals.

Our parenthood story really begins in rural East Texas in 1979. Born within a few months of one another and in small towns about 80 miles apart (which made us neighbors by East Texas standards,) we both grew up with the inborn need to be parents. Some thirty years later, we met in Austin and fell in love. We discussed children early on in our relationship, but quickly filed that discussion in a folder labeled “Someday.”

Born two years before the start of the AIDS crisis, our generation grew up with very few gay men to look up to as examples of how to be in the world. A great number of would-be role models had died, while many of those who survived were shell-shocked from losing friends by the dozen. Coming of age in a world where being queer was dangerous, not to mention social suicide in our small towns, we both learned to keep our heads down. We did our best to blend into the background like wallpaper, avoiding exposure at all costs.

Thanks to folks like Ellen DeGeneres and other positive media portrayals of gay people, the tide turned enough that more of us started living our lives openly. We came out. Still, that acceptance was conditional. The social messaging had changed. Now it felt like we were allowed a seat at the table — as long as we stayed in our lane. We could find some degree of belonging and be valued as the funny friend or the overachieving colleague, but the new ‘deal’ with the straight community came with a mutually understood caveat: “You don’t volunteer information about your relationships, and we won’t ask.” The thought of two men in love still made people too uncomfortable. So, that’s where the line was drawn. We called it ‘tolerance’ back then, and for those of us starved for connection and acceptance, we bought it and went on with life. We settled. Many of us, including myself, built lives around working hard, having fun, looking good and creating a ‘chosen family’ of friends. We stayed in our lane.

I told myself that my life was working just fine and tried to ignore the voice that said, “Something’s missing.” Over time, that sense of being unsatisfied grew from a vague, undefined feeling to a gnawing urge to make a change. Then I met Shannon.

An unintended consequence of being in a healthy, loving long-term relationship was that it challenged that unconscious belief that I didn’t deserve to be loved . . . that a happy ending wasn’t in the cards for me. See, the thing about homophobia is that it always starts from the outside. No one is born with it. But this thing that makes you different, this inexorable part of you that you can’t change no matter how hard you try — it’s only a matter of time before someone sniffs it out and then weaponizes it against you. A bully lobs a slur at you in middle school. You legitimize it with an assortment of hateful messages from the church and the culture at large — and you repeat it all to yourself, kicking your own ass for decades. Now it’s internalized, cementing your view of yourself in the world as inferior. The bully grows up and moves on but you pick up the stick, flagellating yourself with a mantra of “I’m less, I’m dirty. Who’s gonna love me now?”

But something told me to lean into this relationship, unlike the ones before that I had successfully sabotaged in one way or another. I chose to be vulnerable and to accept the love I was shown, and not torpedo it when things got tough. The expectation that I would be alone shattered, which threatened the rest of my twisted self-image. I began to confront some of the paper tigers that had haunted me for so long. I dared to think about what a fulfilled life would look like instead of just cramming my days full of ‘stuff’ as a means of distraction. When I slowed down enough to listen for what I really wanted, it didn’t take long for my lifelong dream of becoming a dad to bubble up to the top. The first place I went was Facebook, since I thought I would find a group for parents pursuing surrogacy and just hover around for a few years and leech information off of those guys. I did find a group called Texas Surrogacy, which was a mix of parents, surrogates and professionals — and as planned, I lurked around like a weirdo.

Maybe a week later, Shannon and I were in the middle of purchasing our first investment property. It was a big deal. We’d saved some money and felt obligated to do something grown-up with it. But there wasn’t much excitement around the idea. While writing the offer, I asked him, “Why doesn’t this feel right?”

Half-apologetically, I told him about my post in the surrogacy group. Without judgment, he asked me why I did it. The dam broke. We cried. We said things we’d been too afraid to say before. We tore up the contract; we knew we were meant to make a different investment. I told him that I’d been exploring the subject online and he agreed that we should start digging. We reached out via the Facebook group and were introduced to Simi Denson, who sat down with us at Blue Star Cafeteria and laid out for us, very plainly, what we would be biting off if we moved forward. The process was daunting. Simi’s style was direct but loving. We both walked away with a feeling that we were exactly where we needed to be. I’ve thought about this a lot since then, and I think that taking that initial meeting is maybe the single smartest thing that I’ve done in my adult life. Simi would eventually become our attorney, friend and trail guide on our journey to meet Jake.

You might be wondering, why did we choose surrogacy? Adoption would have certainly been more affordable and may have gotten us to our goal a little earlier (and let’s face it, we’re getting a late start at this parenthood thing, so time is precious.) We actually plan on continuing to build our family through adoption in the near future. And we will love those children as much as we love Jake. But both of us felt compelled to try for children with our genetics as well. There is something innate within people that wants to continue their family lines. We wanted the same experience that everyone else gets. We refused to stay in our lane.

Getting from there to where we are now was not easy. If you’re reading this, I assume that you are considering whether this process is right for you, and with that in mind, you should know a few things. Gestational surrogacy is fraught with stressful moments. Like us, you may experience loss and disappointment when the first few attempts don’t work. At times, you will feel like you are hemorrhaging cash. You will spontaneously, inexplicably burst into tears at inopportune moments. And you might as well wad up your ideal timelines and throw them out the window; instead, accept that now you are at the mercy of the human body (actually, several of them) and you will have a child if and when God (or biology, or the universe, whatever) sees fit.

But holding our son, I have to work hard to dredge up those memories of the rough spots. We transferred two embryos to our surrogate, one from each of us, and got one beautiful baby boy. When I look at him I see my chin, my grandfather’s smile, but then I look at Shannon’s baby photos and Jake is his spitting image. It is impossible that his genetics are from both of us; we know that. And yet, somehow, we’re both in there.

I cannot share our story without telling you about our angels, because without them, there is no story. Ironically, turning two men into Dad and Daddy took a village of Mommies. To get where we are today took the help of two egg donors, two carriers, one attorney and about a dozen supportive characters (many of them surrogates themselves) who played parts large and small. All are women who devote much of themselves to making the impossible a reality for those of us who need help. They’ve each found purpose in filling empty homes with chaos and giggles. They breathe life into the dreams of others.

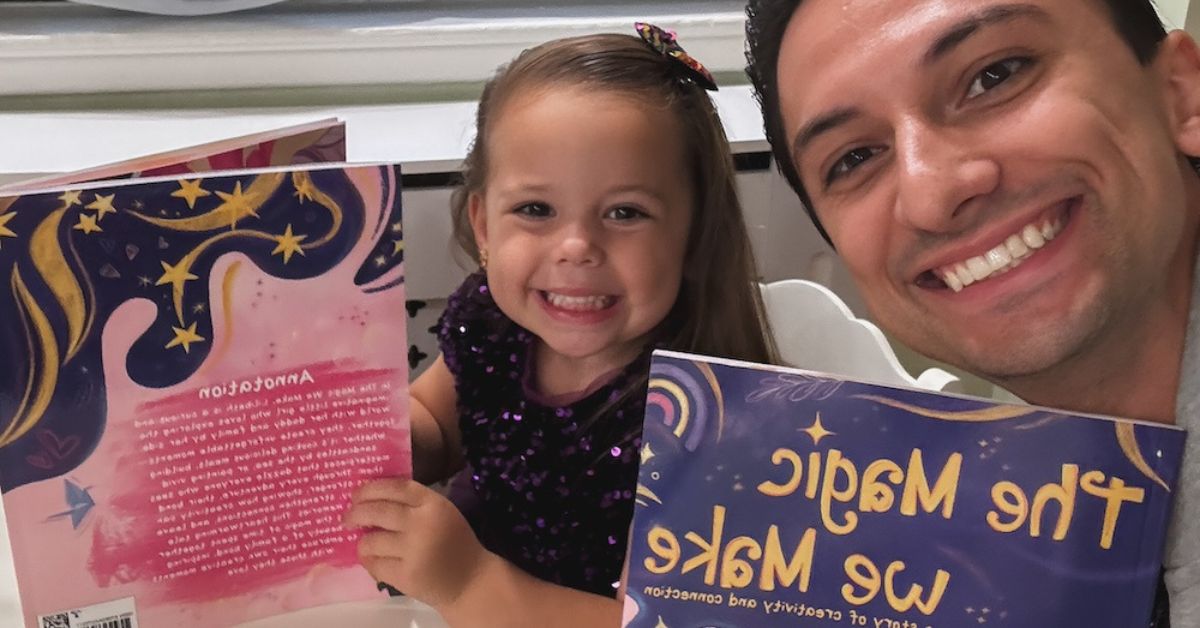

Update: Bradley and Shannon welcomed their second child, a daughter named Ruthie, in January. Jake will be two years old in May.

To help find your path to fatherhood through gay surrogacy, adoption or foster care check out the GWK Academy.