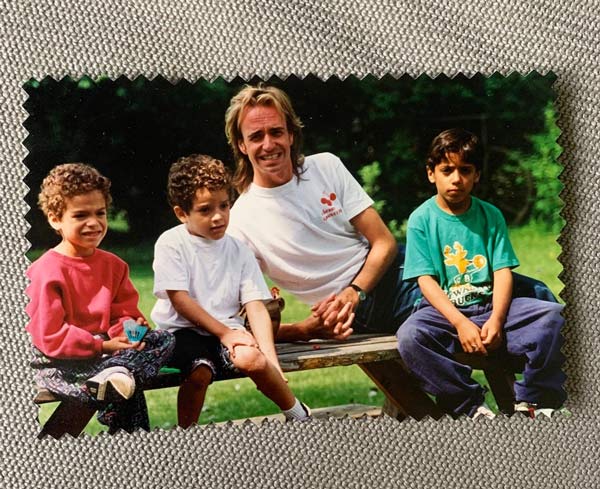

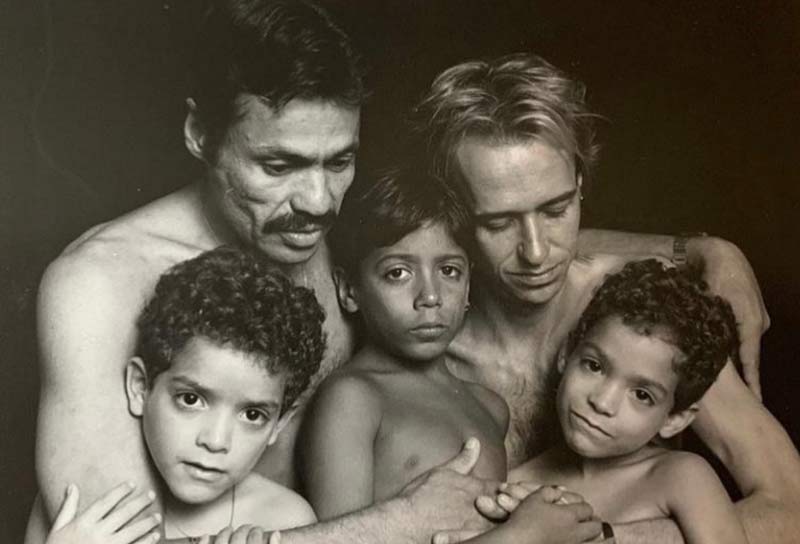

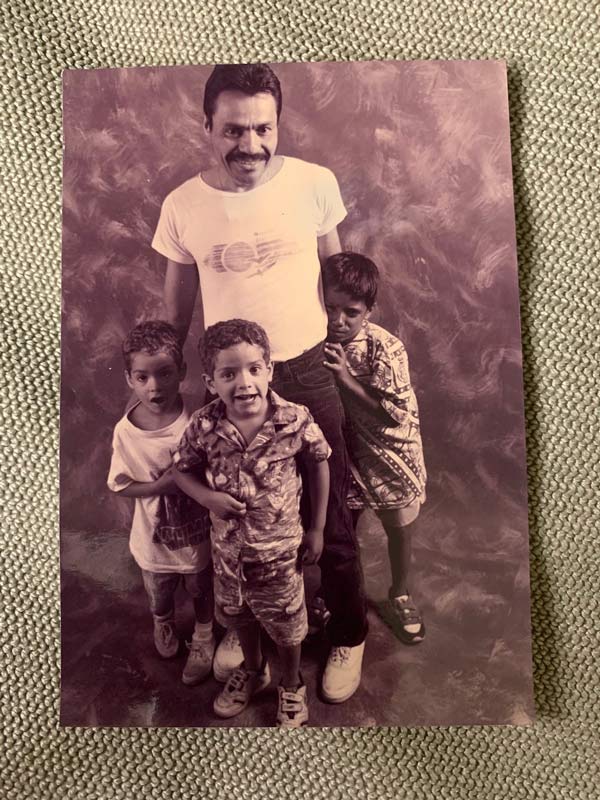

Noel Arce doesn’t remember much about his dads. He was adopted as an infant, and a lot of what he knows about these early years he learned through photographs, like the ones scattered throughout this article. These pictures remind him that he was loved — that he had a good childhood.

Noel and his brother Joel were born into foster care in 1988 and 1987, respectively. When they were just a few months old, or maybe a year (Noel isn’t sure), they were adopted by Steven and Louis, two HIV-positive men living on the Upper East Side of Manhattan, during the height of the AIDS epidemic.

Steven and Louis were already seasoned dads when they adopted the pair. Several years prior, they took in Angel, their eldest, who was also previously a foster child. Noel doesn’t remember much about Angel either; their paths diverged as life and death took a toll on this once complete family. He has, through the years, stayed close with Joel, whom he calls Joey.

To set the stage: in this article’s main image, Joel (bottom left) stares straight into the camera. To his right, and center, is Angel; Noel is on the far right, smirking, with a tilted head. He is held by his dad, Steven, a pensive soul ensconced by the strength of Louis, a man whose dense frame is punctuated by two eyes yielding a view of a soul that’s not ready to die.

Noel refers to his childhood as “painful,” but for that he’s also grateful. While Steven and Louis, like so many gay men of their time, departed this world far too soon, they will always be his dads. And he will always be their son.

“My dads always knew they were going to die,” Noel says. “That’s why they took so many photographs and recorded so many videos.”

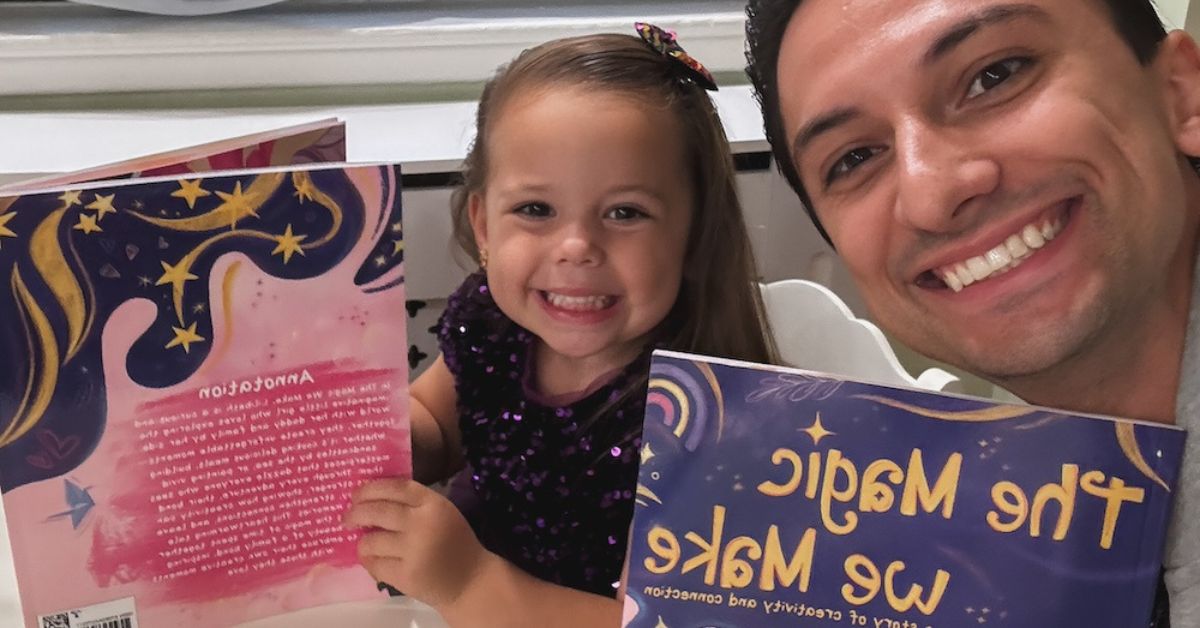

Noel is now 34 years old and living in Long Island, New York. Up until about a year ago, he was a full-time drag queen. “I often wonder what my dads would think of my drag. Would they think I’m funny? Or ridiculous? What about my jokes?” Noel laughs.

Growing up a gay boy of two gay men in the AIDS-gripped throes of the early 1990s in New York City has the potential to read as a plot to any number of movies and Tony Award-winning musicals — but this was reality; Noel’s unique reality; a reality which came crashing down around him in the spring of 1994.

Noel was young before his dads left him, and was still young at the time they passed. He said, “sometimes my memories are like a train, it gets smaller and smaller as it pulls away.” As such, the memories are fewer and further between than what he’d like.

He can still smell warm cranberries baking during the holidays and the salty taste of Play-doh smushed along the webbings of his fingers in the basement of the family’s summer home upstate. He can picture the wallpaper in the living room and still hear the sound of his dads’ voices calling from the other room.

Noel wants to visit the house, to walk the stairs down into the basement and touch the wallpaper again, to smell the air and wait for the memories to flood his brain. He shared, “the house is still there, but it’s different. The new owners have changed it quite a bit and it’s not the same.”

His favorite childhood toys were Barbies and, of the few natural memories he does still possess from that time, key ones revolve around dressing them up in matching outfits to his own. “I’m so lucky to have had the childhood that I did. My dads let me wear girl’s clothes for Halloween, and just be myself,” Noel shared.

At school, the kids were well-liked by their peers and lived normal lives, filled with love. Among a vast collection of personal photo and video mementos — a sort of documentation of life in their final years and days — Steven and Louis recorded a one-way conversation intended to be played in the future, long after they died. In it, they spoke to Noel, Joey, and Angel. To Noel, specifically, they discuss always knowing he was gay.

Louis was a social worker and property manager by occupation and an activist by trade. Among his many touchstone achievements, in 1994 he was posthumously given a Gold Key Award from the Bailey House of NYC, honoring his work in assuring that a certain percentage of all new buildings erected through his Manhattan Valley jurisdiction would be reserved for people living with HIV and AIDS.

Not much is known about Steven.

“As a gay man myself, I really respect them. To be gay during that time and to be living with AIDS when it really wasn’t easy,” Noel said. The admiration he feels for his dads is palpable; recently, Noel has been finding new ways of connecting with his fathers and their experience through queer documentaries. Educating himself on the origins of the queer liberation movement and AIDS history through anything streamable.

“I wonder what it must have been like for them. To be strong like that,” he said.

* * *

Around May of 1994, Steven and Louis’ emergency room visits became significantly more frequent. Noel and his brothers would visit his dads in the AIDS ward of the local hospital up until one day the visits stopped.

On June 18, 1994, Steven died; five days later, on June 23, 1994, Louis also succumbed to late-stage internal trauma caused by AIDS. The devoted partners and dads passed within a week of each other.

Noel wasn’t at the hospital when either of them died, and neither were his brothers. Though he vividly remembers coming home from school in the early afternoon to his uncle and aunt (Louis’ brother and his wife) whom had been staying at their apartment watching Noel and his brothers. They brought each of the boys into their dads’ room one by one. That’s when he learned the news that would change, and shape, his life forever.

Noel remembers sitting on the edge of the bed as he heard the words telling him his dads were gone. They were dead. They had died of AIDS. Noel remembers being sad, and distinctly recalls feeling compelled to cry, to put on a show of sympathy. He forced the tears. He said, “I just felt like a dog. A dog performing for this room of people, doing what they were expecting of me. I cried because everybody else was crying.”

He was a little scared, and certainly sad — but mainly confused. The final days and those thereafter were perplexing and frightening. After Steven and Louis died, the boys went to live with Louis’ brother and his wife on Long Island, just outside the boroughs.

Shortly thereafter, Noel began referring to them as “mom” and “dad;” as his parents.

And still, an already fractured family began to further split. During the late stages of Steven and Louis’ illness, Angel was sent away for severe and worsening behavioral issues. Noel never heard from him again.

“I don’t even know what happened to him,” Noel said. What he does know is that about a decade after Angel — who was also HIV positive — left, “my mom came across him on the streets of New York,” Noel said. “She told me that he had stopped taking his medications and did not look good.”

The family figured Angel may have been homeless for some time, while simultaneously slipping further into sickness and mental health challenges. “Honestly, I’m not sure if he’s still alive,” Noel said. “Last I knew for sure, though, he wasn’t doing well.”

Until recently, Noel hasn’t shared his story with many. For too long, he’s felt burdened by an amalgamation of pain and shame. “I’ve always feared what people would think. I guess my close friends always knew, but this is my first time telling anybody else.”

That all changed when Noel shared a photo with @atheaidsmemorial on Instagram. It quickly went viral. Since then, Noel describes the reaction to his story as simply “amazing.”

Now that he’s had time to reflect, Noel is proud of his decision to make his story public — to educate the masses on a different kind of nuclear family. He says, “leaving their stories untold would mean that nothing will ever get better. That’s why I decided to share their lives.”

* * *

At the time of their death, in 1994, Louis and Steven were deeply committed to a messy, late-stage battle against AIDS. By this point in the pandemic, the crisis had entered it’s thirteenth year and was about to claim it’s quarter-of-a-millionth victim. Pneumocystis pneumonia was tightening airways and Kaposi’s sarcoma was maiming flesh; “GRID” was now “AIDS” and research dollars continued to trickle down a stream of compulsion. For the first time in history, gay men were above the fold in a world desperate to do anything but read the headlines.

In 2021, on this, the fortieth year of the AIDS epidemic, forty million lie dead.

Then, in March 2020, the world stood still for a moment. We all watched, some of us again, as a new kind of epidemic unfolded. We held our breaths, and then took a collective exhale once we realized that maybe, just maybe, just like before, we could get through this. COVID-19 has ravaged the globe for just about two years; conservative estimates state a current death toll at somewhere around 5 million lives, with actual numbers likely a great multiple of that.

Noel is doing well, though. Like the rest of us, he’s getting by. He temporarily lost his job as a drag queen early on in the current pandemic, when we once again jettisoned bastions of countercultural significance in the name of public health. He now works as a brand manager for a luxury men’s fragrance line. A coronavirus-generated career change that has ironically allowed him to maintain a personal brand of panache through the generation of a different kind of aerosol.

* * *

The smell of Play-doh will likely always have the power to transport him to his childhood, more often unwillingly than not. To this very day, the taste of cranberries and certain patterns of wallpaper give his brain the ability to transcend the laws of physics and careen down a wormhole to simpler times, sans tragedy but also lacking retrospect

Decorating a Christmas tree in December can still return his brain to the mid-nineties, where memories of hanging homemade ornaments on a Balsam Fir seem to unlock themselves; for a moment, he’s with his dads again and they’re about to open presents and count the cookies nibbled by Santa. Moments located deep within his subconscious, somehow striking an uncanny parallel to actual holiday guests from faraway cities whom we only see once per year — always seeming to stick around for not enough time and just long enough to cause us some type of pain.

“I’m a good person,” he shared with me. “I know I am. And at the end of the day, and through this all, I’ve also come out strong. I’ve fought through a lot of things and my dads would certainly be proud. They would be proud of my brother Joey too; he’s been through so much.” Noel values kindness above most other things.

He believes that adversity breaks people away from derivative molds and reshapes them into strong, unique players — the type of people he most prefers. He continued, “Those who have been through struggle and come out the other side are most compassionate.”

He also thinks of Steven and Louis often. He shared a follow-up thought: “If I could talk to my dads now, if I could say anything to them, I would just want to know what they think of me. I really, really hope I make them proud.”

By the time he hung up the phone, Noel seemed happy, if not a little eager to tell his story to the next person. And then the next. The power of owning our pain and taking credit for our own resilience has an ability to assuage the largest doubts to at least some degree, it seems.

He even texted me an eager “thank you!” and we promptly followed each other on Instagram — which I’ve decided is Twenty Twenty-One for “I don’t want to forget you.” As Polaroids become PNGs and communication morphs inherently further away from an analog medium, there’s something reaffirming about claiming our ephemerality through a quick “follow” and a regular “like.” I go ahead and “double tap” a few of his pictures, as he does mine.

This is how our stories will continue.