I’ll never forget the morning of January 28, 1986, where, along with the rest of the world, I excitedly watched the Space Shuttle Challenger soar into the sky and then, shockingly explode just 73 seconds after take-off. I was 8 years old and didn’t understand what was happening. I assumed smoke and fire was to be expected, just like during lift-off. But what I remember most vividly from that fateful morning was how quickly and frantically my elementary school teachers ran to turn off the TV. Their first instinct was to shield my first grade class from the sad reality of what had just happened.

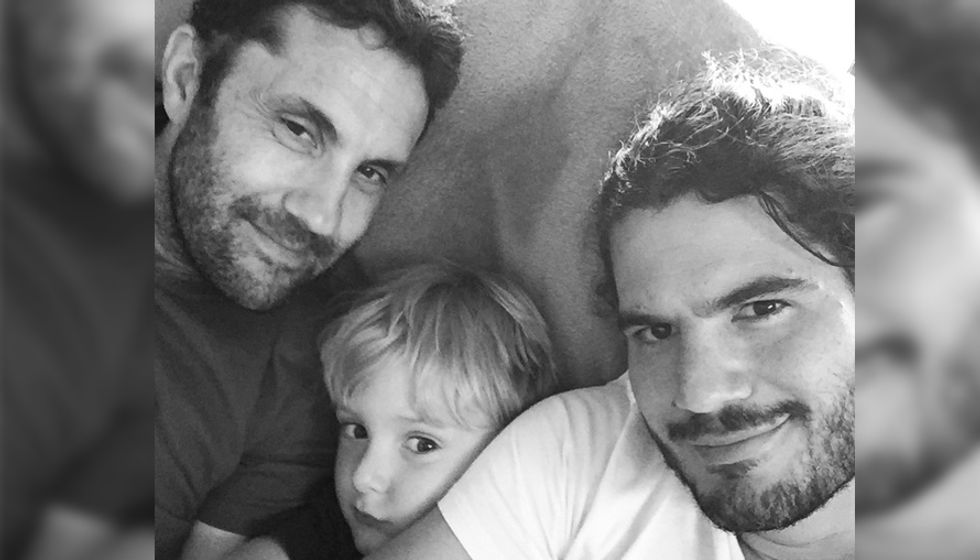

Cut to 30 years later, I’m now the father of a five-year old boy, living in a time where there seems to be inexplicable worldwide tragedies occurring on a daily basis (just as I’m typing this article, a CNN notification popped up on my phone alerting me of another terrorist attack in Nice, France). It feels like every time I see a flag now it’s at half-staff. From mass shootings and terrorist attacks to natural disasters and that puffy orange troll with bad hair, our world is in bad shape. It’s downright frightening. And like my first grade teacher’s, my first instinct is to cover Max’s eyes and shield him from these horrific events. After all, he’s just a little boy — far too young to understand these complicated matters.

Our instincts tell us to avoid discussing certain current events within earshot of Max; to control his TV viewing and radio listening; and to limit his exposure to other forms of 24/7 news content. Are we doing the right thing? Or are we simply avoiding tough conversations? How do we help our children feel secure when we ourselves feel insecure, vulnerable and helpless?

My husband and I turned to a family therapist for answers. She explained that it’s not always as easy as not talking to kids about these things. Instead, she armed us with some helpful tools to address these sensitive matters with Max in a delicate, age-appropriate manner. Hopefully, this information can act as good rules of thumb for you and your family.

Disclaimer: I am by no means an expert. What I’ve outlined below is based on personal research, professional advice and some common sense.

Children aged 2 to 6:

Pre-school aged children react more to their parents’ distress than to anything else, so it’s important to monitor your own emotions when your child is around you. I know this to be true. Even as little as 3 years old, Max would pick up on everything I was experiencing and feeling.

For this age group, experts suggest only addressing these scary events if kids bring it up first. And if they do, it’s advised to keep things black and white — you don’t have to give them more details than they ask for. Because while the world can be a cruel place, younger kids need to be reassured that this isn’t happening to them and won’t happen to them. For this age group, it’s probably smart to avoid exposure to news. The way that 24/7 news media replays the same frightening footage can make a young child think that a single tragedy happens over and over again.

Don’t be afraid to ask questions. You don’t know how they actually feel inside, so try to understand their feelings about what happened. You can ask, “What did you hear? What do you think about that?” That’ll help inform what you should do or say next. If they want to know more, use words they’ll understand, such as “bad man” and “hurt” as opposed to “shooter,” “gunman” or “tragedy.” If they are scared, ask what they’re afraid of. If the news event happened far away, you can use the distance as a way to set their mind at ease.

You can also use these events as a teaching moment, as an opportunity to model compassion. Explain how you can donate to relief organizations to help the families most affected by these terrible events.

Children aged 7 to 12:

Once kids are in elementary school, certain news stories will be unavoidable, especially with the increasing number of kids with their own smartphone. When talking to them, just run through the main points of what happened. Children of this age group are comforted by facts. The who, what, when, where and why should guide your discussion. At this stage in their lives, they’re starting to become concrete thinkers, so when possible, it’s helpful to offer concrete answers. But remember not to be dramatic or use words that’ll scare them. If you stay calm and rational, they will, too.

And to help kids make better sense of what they hear, it helps to put news stories in proper context. Explain that certain events are isolated while other events are related to something bigger. It’s also important to reassure them that events like these are very unusual and that there are good people trying to help prevent similar events in the future.

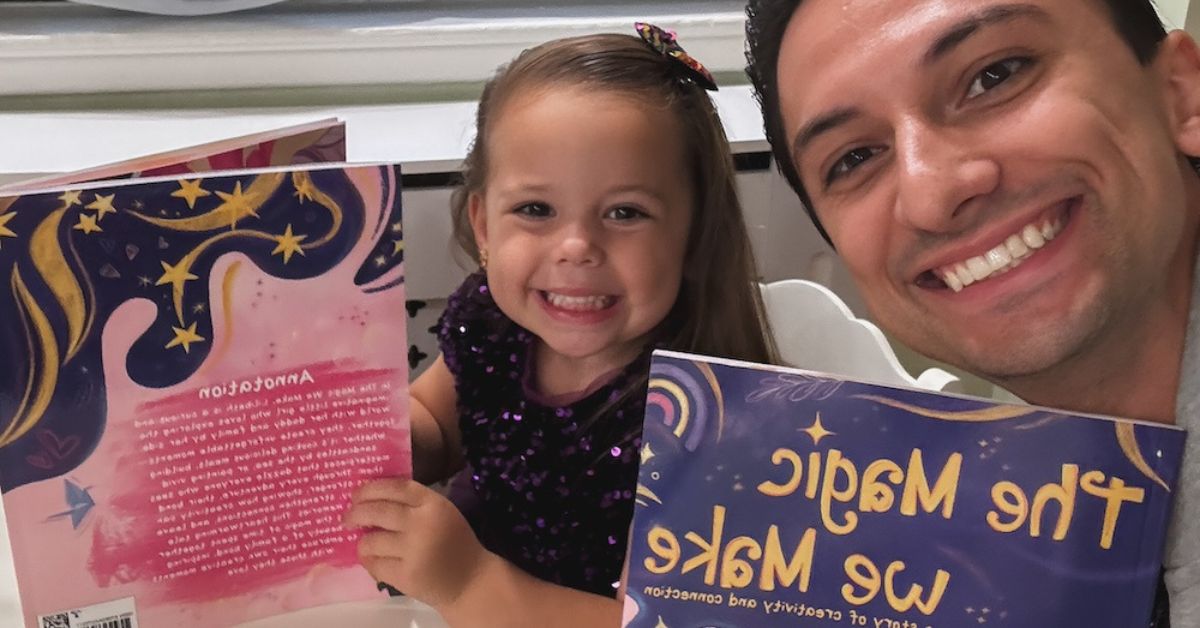

If talking about things makes your children’s fears worse, try to distract them. Do something together that they like doing. Watch their favorite lighthearted film, go for a bike ride, snuggle and read to them, play a video game together, anything that reaffirms to them that it’s okay to think about other things and get back to their normal routine.

By age 7, your child should know how to reach you at all times. Confirm this. Having your cell phone number and knowing how to use a phone goes a long way to making you — and your kids — feel confident.

Children aged 12 to 14:

At this age, it’s okay to engage your children. News like this is easier to receive from a parent than a friend. You can start by asking them if they’ve heard about the event. Experts suggest that simply being there to help them absorb the news in an environment they feel safe, is more important than having all the answers. By this age, children understand the difference between the good guys and the bad guys.

As they approach the teen years, tragic news can cause some kids to spend more time with friends, while others might want to spend more time alone. Different kids will process the news differently. But nobody knows your child better than you, so use your natural instincts and let them know that it’s normal to feel and act the way they are.

Ask them what their biggest worry is. If the news event has them questioning their own safety, take the time to review the plans in place to keep them safe. For example, show them where the fire extinguishers are stored. Explain the best place to gather during an emergency, etc.

High school-aged children:

Once kids are in high school, it’s very likely that they get their news from social media and friends. While they probably just know the highlights, it might be a good idea to sit them down and explain what’s happening in more detail in order to get at the underlying reasons for these types of events. These are very complicated issues that usually aren’t quickly solvable, so it might be a good idea to share your feelings with your children — it’s a good way to keep the dialog going without making it all about them.

Experts suggest speaking to teenagers in terms of probabilities. They’re old enough to not believe absolutes such as “This will never happen to you” or “I promise you’ll always be safe.” So instead, you might want to speak in facts or percentages of just how unlikely it is for something like this to ever happen to them. For example, “At the 27,000 public high schools in the United States, there have been 9 mass shootings.”

Lastly, even in their teens, they’re never too old to be reminded what to do in case of an emergency. Tell them where they should go if they can’t get home or who they should call if they can’t reach you.

If they feel as helpless as you feel, suggest doing something kind for others. Little things like picking up groceries — or shoveling the driveway — for an elderly neighbor reminds them that there are still kindnesses in the world. In a small way, it can reduce the feeling of helplessness.

At the end of the day, life is uncertain, but the one thing that is certain is the love we have for our children. Regardless of what happens in the world, the best thing we can do as parents is be available. I believe that makes the biggest impact in times like these.

To help find your path to fatherhood through gay adoption, surrogacy or foster care check out the GWK Academy.