It was clear from the beginning that Tom Gantt, 43, had an activist on his hands. On their very first date, Juan del Hierro, 36, excused himself for a moment – not to run to the bathroom to check his hair in the mirror or to sneak a breath mint like a regular gay – but to jump onto an organizing conference call.

This was 2008, and Florida was facing an anti-LGBT marriage amendment in the form of Amendment 2. And Juan was doing everything in his power to stop it. This included, Tom would soon learn, volunteering 40+ hours a week at SAVE, an LGBT rights organization based in Miami-Dade county, Fla., where I was also employed at the time as a field organizer.

I had the pleasure of getting to know Juan, and later Tom, over the many, many hours we collectively spent organizing against the marriage amendment in 2008. But with 62 percent of Floridians voting in favor of the marriage ban, we would, unfortunately, lose this battle. Though none of us could have predicted it at the time with their relationship still so new, Juan and Tom would help ensure, eight years later, that we wouldn’t lose the war.

But I’m getting way ahead of myself. Back in early 2008, Juan and Tom had just completed their first date, each excited by the relationship’s prospects. “The fact that Tom was patient and let me take a 15-minute break from our date for [an organizing call],” Juan said when we caught up by phone recently, “told me he was special.”

And Tom’s patience, garnered no doubt through more than a decade’s worth of teaching in Florida’s public schools, would certainly come in handy over the years; this was the first but definitely not the last romantic dinner that the couple would have interrupted by a call to activism.

Getting Their “Gill Baby”

“I always knew I wanted to be a daddy,” Juan explained, who works as a licensed Unity minster and as the director of minister empowerment at Unity on the Bay, a spiritual community-based in Miami. He was so certain, in fact, that the desire to have children was a strict litmus test for would-be partners.

“I had a conversation with Tom about having kids when we first met,” Juan said. “Like not even two months in.”

“And I didn’t know at first,” Tom admitted. “I was teaching at that time and felt like I was already raising kids in some way.”

But for Juan, raising his own kids was something he’d always wanted for himself. “So I said, well, you can have a few weeks to think about it before we break it off,” Juan said. He paused a moment before adding, with a little laugh, “I was a little scary.”

Ultimately, Tom was not opposed to the idea of starting a family and quickly got on board as the couple’s relationship progressed. But Juan and Tom would have to wait a while before they could become parents.

In 1977, the Florida legislature passed a law stating, “No person eligible to adopt may adopt if that person is a homosexual.” The law, the first of its kind in the country, was largely the brainchild of Anita Bryant. A one-time singer and winner of the Miss Oklahoma beauty pageant, Bryant is now best remembered as a fear-mongering blowhard who squandered her fame and fortune campaigning on behalf of anti-LGBT causes in Florida and elsewhere across the country. (It might not be put exactly like this in Bryant’s Wikipedia article, but it should.)

Incredibly, Bryant’s ban in Florida survived several decades’ worth of court challenges, meaning Juan and Tom had the misfortune of living in the state with the harshest anti-LGBT adoption laws in the country. Whereas states elsewhere in the country, such as Arkansas and Utah, targeted the LGBT community by prohibiting adoption by “unmarried couples,” Florida’s ban targeted LGBT individuals as well.

Florida’s ban was finally overturned in 2010 when a state appeals court, in a court case named in re: Gill, found it to be unconstitutional. The plaintiff in this case, Frank Martin Gill, had petitioned the court in 2007 to allow him and his partner to legally adopt two children they had been raising as foster parents.

Fortunately for Juan and Tom, and all of Florida’s LGBT community, the governor and attorney general decided not to appeal the decision, which had the effect of legalizing gay adoption statewide. (In a symbolic act, the Florida legislature recently passed, and Governor Rick Scott signed into law, a repeal of the adoption ban this past June 11, 2015.)

“It’s funny, because we had just started the adoption process when this decision came down,” Juan said, “so the ACLU refers to all the children that were adopted from 2011 to 2012 as ‘Gill babies,’” he said, in reference to the plaintiff in the case, with whom he and Tom are friendly.

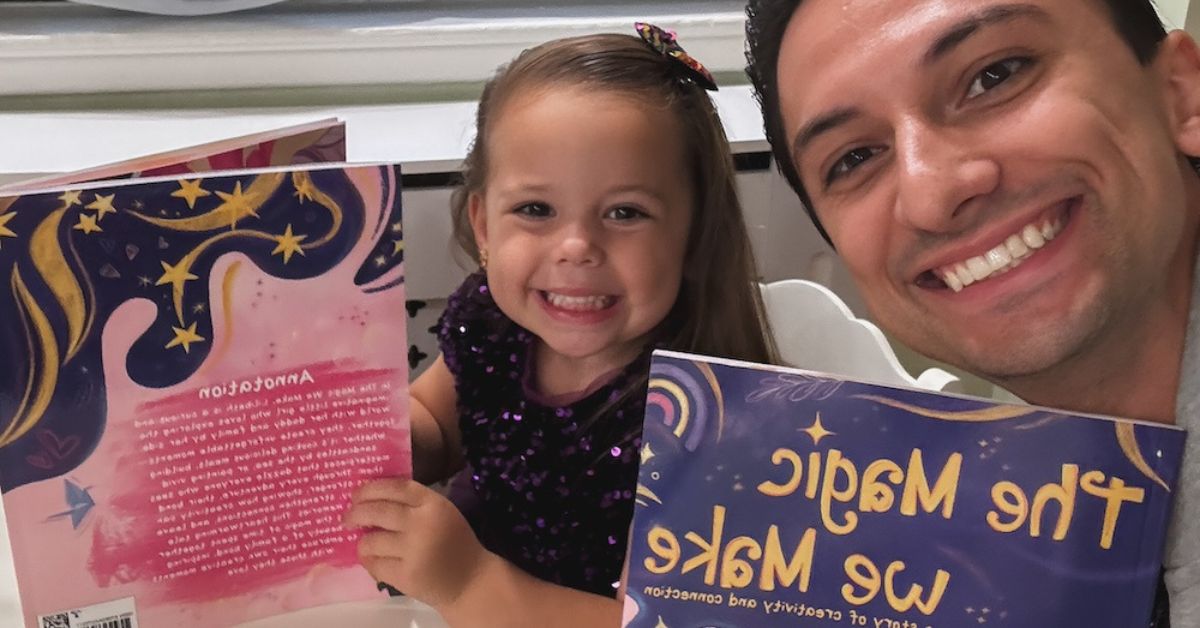

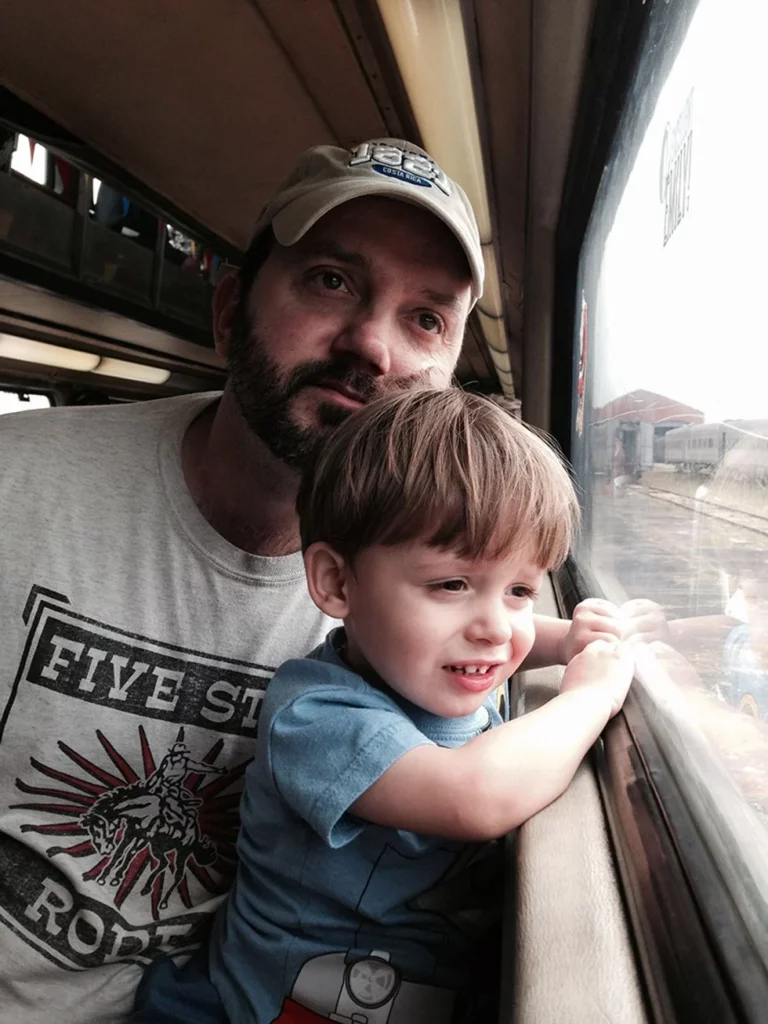

And soon, Juan (photo above, left) and Tom (photo above, right) would welcome their own little Gill baby, Lucas, now 2½ years old, into their family. Juan and Tom couldn’t have been happier, but, as a same-sex couple living in a state that didn’t yet recognize same-sex marriage, they also knew they might faced their fair share of complications.

“All of the paper work we did was as if we were two single men living together,” Juan said, who was the one to “officially” adopt their son Lucas. Though Juan was able to sign over parental rights to Tom directly after, the two did not have equal rights under Florida law. “We receive a monthly stipend from the public adoption,” Juan explained. “If I were to die, the benefits would go away. They’re not transferable.” Other non-transferable benefits included college tuition and health care benefits for 18 years.

“It was quite a chunk of change,” Tom said of the benefits he and Lucas could be denied.

In 2014 the ACLU approached SAVE – where Juan was serving as a member of the board of directors – about finding plaintiffs to sue the state to bring about marriage equality. The couple jumped at the chance to help bring about change.

“It was just the right time,” Juan said, who added that, this time, they weren’t acting solely out of an inflamed sense of social justice. “All that denying us equal parenting rights meant that Lucas could be hurt. It was personal. That’s what this is all about.”

The Super Volunteer

On March 13, 2014, the ACLU officially announced a lawsuit, filed in federal court, on behalf of eight couples who had been legally married in other jurisdictions where same-sex marriage was already recognized. (Juan and Tom were legally married in Washington, D.C., in December 2010). Among the eight couples, Juan and Tom were one of two LGBT couples with a child, and the only gay male parents in the lawsuit. They were enlisted in part for this reason – to help demonstrate the deleterious impact of marriage discrimination on LGBT families in Florida.

Originally, Juan and Tom thought they might be more involved in the legal aspects of the case. “But we weren’t really involved; we never even went to court,” Juan said, with a hint of disappointment in his voice. The court proceedings, he elaborated, were held almost entirely over the phone, through conference calls.

The plaintiffs were not asked, or even encouraged, to be on these calls. But Juan is not the type to sit idly by while judges and lawyers debate the fate of his marriage and family. So, in his copious free time, he asked to be included. “I was the only plaintiff on [the calls]” he said, almost embarrassed. “But you know me, I have to be involved in everything.”

What the couple lacked in legal involvement, however, they certainly made up for in media.

“It was overwhelming,” Juan said with a sigh, “all the media stuff.”

Juan and Tom are no strangers to the spotlight, so hearing this, from Juan especially, surprised me. The couple was front and center during the fight against Amendment 2, the state’s anti-LGBT marriage amendment, and Juan has been part of the Spanish Speakers bureau at GLAAD, the LGBT media watchdog group, for many years. Had Mr. “Involved in Everything” finally reached the limits of his activism?

“No, not at all,” Tom said, laughing. “Let’s just say that Juan really wanted to be much more in the forefront.” There were times, Tom explained, when the couple would be out to dinner or at an event when they’d receive an interview request. Just like their first date, when he excused himself to jump on an organizing call, “Juan would always be ready to run back home to do the interview,” Tom said. “I always appreciated it once we were there, but then other times, I was like, why can’t we just say no?”

Was Tom saying he had regrets about joining the lawsuit?

“No, not at all. But I’m …” he continued, then pausing a moment to gather his thoughts. “I didn’t want to change our lives to make it fit the situation, does that make sense? It was frustrating for me at one point.”

Hearing this from Tom, I felt a sudden pang of guilt. Juan and Tom, together, were two of the most dedicated volunteers I worked with during my time organizing against Amendment 2. But Juan is was what we in the business like to call a “super volunteer,” which meant, basically, that he never says no. He worked just as hard, and probably harder, than those of us that were paid to be there. And at the drop of a hat, I could count on him to help lead a last minute phone bank session or canvass training, or even to lend an ear after a particularly hard day in the field. If he thought what was being asked of him would further the movement in any way, he would drop what he was doing, and he be there.

I’m embarrassed to admit this now, but amid our round-the-clock workweeks, I had never really stopped to think about the toll this type of commitment could take on a relationship or a family. I know I certainly wasn’t maintaining healthy relationships during that campaign; maybe there’s a reason why most of the community organizers I know are single?

“It created some tension sometimes,” Juan admitted. But from Juan’s perspective, he wasn’t only heading a do-gooders calling to serve his community. “I’ve always seen this all as something we were doing for our family.” But finding the right balance between family and community hasn’t always been easy.

“Sometimes [Tom and I] would have lots of, um …” Juan trailed off, choosing his words carefully, “let’s say ‘discussions,’” he said finally, making all three of us laugh. “We’d have to decide whether we should spend our evening having a family dinner, or if the priority was to do something for the community.”

Tom, too, felt this tension. “We needed to making sure we were out there enough to get the message across,” he said, “but then sometimes you need privacy in order to be the family you’re trying to be.”

Tom also worried at times about his family’s safety as a result of the intense media presence. “There’d be press outside our house at times,” he explained. “Our neighbors are cool, but you never know who isn’t. What if someone against us was like, hey, that’s where those guys live that overturned the marriage law. You need to think about security, especially with Lucas. We want to protect him from all that.”

Looking back, despite the occasional “discussion,” both are unequivocally happy with their involvement in the ACLU lawsuit.

“I was just amazed and surprised with how easy going Tom was with the whole process,” Juan said. “Except for a few things here and there,” he added, laughing.

“And I’m glad Juan was a little stubborn,” Tom said. “He would even let me say no to some things,” he joked. “Rarely,” he teased, “but sometimes.”

A Star Turn Abroad

The media surrounding Juan and Tom’s star turn as plaintiffs in Florida’s marriage equality case extended much further than local and state outlets. Juan, who is originally from Ecuador, also faced intense interest from international media as well. The most extensive foreign media story on the family came in the form of an hour-long news show in Ecuador that profiles different Ecuadorians with interesting stories living abroad. For several days, the family had camera crews and reporters following them around at work and home. The family discussed their adoption of Lucas at length in the segment, as well as their involvement in the ACLU lawsuit.

It was exciting for Juan and Tom to have the media interest in their family extend internationally. “As a biracial gay couple,” Juan said, “it was great to have so many Latino countries see us as a family. Lucas is the cutest kid in the world, and that world got to see him being happy and healthy, in a gay household. You can’t help but think differently about a gay family seeing that.”

But some members of Juan’s family weren’t as pleased with the media attention.

“It’s created tension in the family,” Juan admitted, “and if anyone has had to bear the brunt of this all, it’s been Grandma,” he continued, in reference to his mother. Juan’s mother, who is currently living with the couple, is no longer on speaking terms with one of her brothers as a result of their high profile in the ACLU lawsuit. She has also had other friends and family members speak negatively about her support for Juan and Tom’s family.

“They think that she, as a grandmother, shouldn’t be okay with it,” Juan explained. “We are too open and too proud for them. For me, I’m like, good riddance,” he continued, who isn’t necessarily close to his uncle, or others in Ecuador who have taken issue with his sexuality. “But seeing it affect my mother is so hard. She’s being ostracized and having relationships break, all as a result of us.”

* * *

On August 21, 2014, U.S. District Judge Robert Hinkle found Florida’s marriage ban unconstitutional in the case brought by the ACLU. A stay was put on that ruling, which expired on January 5, 2015, which meant, as of this date, marriage equality had officially come to Florida.

On May 9, 2014, Juan and Tom, along with the other seven plaintiffs in the case, were presented with a “Champion of Equality” award from SAVE, the LGBT rights organization where I had first met the couple while campaigning against Amendment 2.

I gave the couple a hardy “Congratulations!” on the phone when they told me this news.

“Well, it’s funny,” Juan said in response, “I remember thinking, all I did was sign on the dotted line, and I get an award? I didn’t do…”

“Whoa, wait a second,” I said, cutting him off. Juan’s trademark modesty was endearing, but I couldn’t let him get away with it this time. There were few other couples who had dedicated as much time and energy to making marriage equality a reality in Florida. As a couple, he and Tom had knocked on more doors than a missionary, made more phone calls than a telemarketer, and endured enough media attention to make them honorary members of the Kardashian family (except Juan and Tom’s was deserved).

“Well, okay, yes,” Juan said, a little uncomfortable with the praise. “But what I mean is that so many people worked so hard for this victory that never got recognized. You fought for this, too, and so, so many other people. It’s just interesting what becomes a part of history.”

This is as much as I got either Juan or Tom to claim credit for this victory. But, fortunately, the couple is far less modest when discussing Lucas’ role in helping bring about marriage equality in Florida. “We’ve kept a record of every mention of the lawsuit in the media. Every blog, video, news clip,” Tom said, proudly. “We’re keeping it all in one place for Lucas, so he can understand the role he played in helping make all this happen.”

Juan also pointed out that, since the Supreme Court stayed their lawsuit, it is now in the Library of Congress. “And I think it’s great that Lucas can go there when he’s older and see his name,” Juan said. “He’ll be able to know that he was a part of history; that all this took place because of him. He can always be proud of that, the love and power of who he was as a baby to change the situation for so many.”

And with Juan and Tom as parents, there’s no doubt in my mind that Lucas’ years of change-making will not be confined to his toddling years.