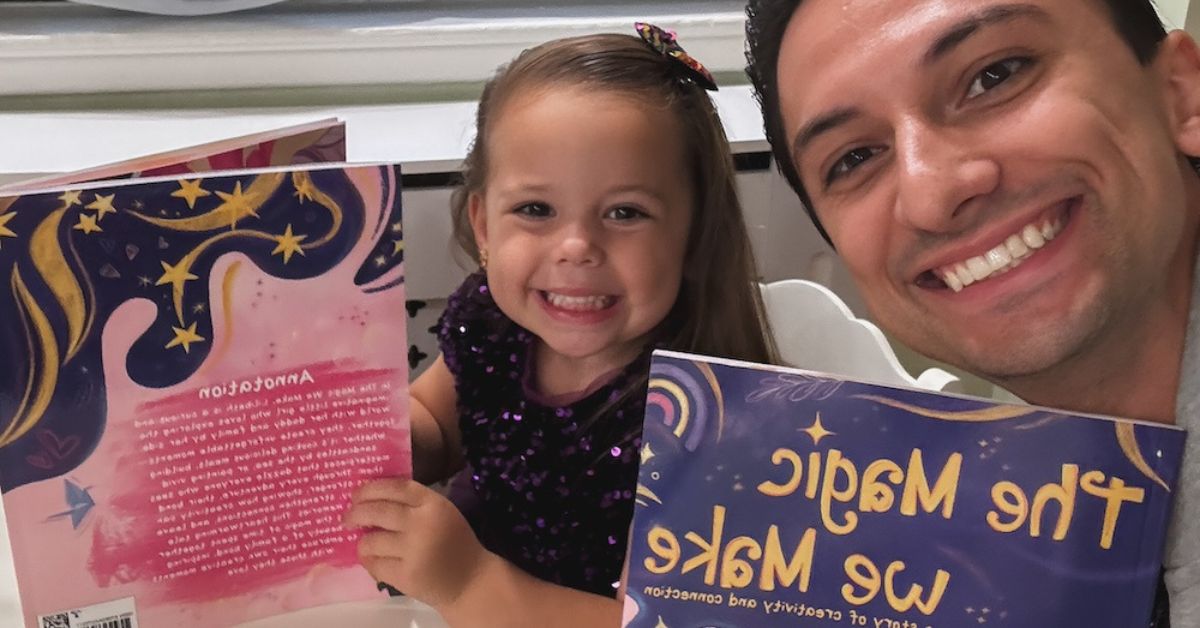

Photo credit: Sarah Clapp

Editor’s note: This story was originally published in 2015.

Several months back, I was hours deep into a particularly painful bout of Internet procrastination when I stumbled upon a link a friend had posted to his Facebook wall, accompanied by a single descriptor: “Powerful.”

I clicked on the link to find a photo series, by Tatjana Plitt, which featured intimate portraits of military families, mostly taken in the families’ bedrooms. In one, an Army man stares at the camera, stoic-faced and dressed in fatigues, while his spouse grasps tightly at his arm. In another, a mother stares down at her son, while he helps button up her uniform.

But what made this series “powerful” and unlike other projects seeking to honor military families is that it exclusively featured LGBT service members. Plitt was able to publicly share images of LGBT military families, of course, only after the downfall of the Clinton-era “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell” [DADT] policy, which banned LGBT people from serving openly.

“It is time [for LGBT service members] to be seen and honored as full citizens,” Plitt says in a video that accompanied her project, which she titled “Gay Warriors.” Touched by the photos, and thankful that a bout of procrastination led to a rare moment of inspiration, I reached out to Plitt. The images were powerful on their own, but what were some of the stories behind the families pictured in these portraits, I wonder?

Two Military Guys Walk Into a Bar …

That Johnathon and Joshua’s paths crossed at all is pretty remarkable. Fourteen years ago, Josh, 42, a medical doctor in the army, was stationed in Fort Lewis, Washington at the same time that Johnathon, 43, was a travel nurse in the area.

“Johnathon was moving around so much at the time, receiving a new assignment in a new city every year or so,” Josh explained. “But we just happened to be at the same gay bar in Seattle one night.” Josh noticed Johnathon first, but was too shy to approach him. So instead, he sent his friend, who turned out to be the worst wingman in history. “They briefly became a couple, actually,” Josh laughed, “But it didn’t seem to be a good fit. So then [Johnathon and I] finally went on a date.” Fourteen years on, they’ve been together ever since.

Though Josh wasn’t sure that he wanted to be a father, Johnathon always wanted kids. “After being with him for long enough,” Josh said, “I kind of saw that he’d be such a great dad, and I wanted him to have that experience. I came around to it, and am really glad that I did.”

The couple started the adoption process in 2009, as soon as Josh returned from a deployment in Iraq. “We focused on adoption from the beginning,” Josh explained. “Surrogacy can be more expensive, and means one of us would be biologically related, but not the other.” These weren’t major issues for either of the men, “but adoption just made sense for us,” Josh said.

However, with DADT still in full effect, they knew adopting wouldn’t be easy. They’d likely have to conduct a single parent adoption, for instance, meaning both dads wouldn’t be able to be listed on the birth certificate. How do you decide which of you is going to be a legal stranger to his child?

Still, the couple was ready for fatherhood, and looked at the difficulties of adopting under DADT as an unavoidable evil. And so, soon after Josh’s return from Iraq, the couple dove head first into the adoption process, which as anyone who has undergone the experience will tell you, can be a protracted one. But, in Josh and Johnathon’s case, the lengthiness of the adoption process came with one substantial benefit.

While Johnathon and Josh busied themselves with completing all the bureaucratic work associated with adopting – home studies, background checks, fatherhood seminars, and filling out a seemingly endless supply of paperwork – the repeal of DADT was snaking its way through Congress, and finally passed both houses in December of 2010. But the enactment of the law would have to wait another year, while the secretary of defense and the chairman of the joint chiefs of staff conducted a study to prove to the repeal’s detractors what the rest of us knew all along anyway: LGBT people serving openly in the military would have no impact on military readiness. President Obama finally signed the repeal into law in September of 2011.

By the time of the repeal, Johnathon and Josh had just finally completed all the necessary steps to enter the adoption pool, so they wouldn’t have to worry about adopting under the discriminatory policy. It also meant something else hugely beneficial for the couple: They no longer needed to hide their relationship from the military. They wasted no time making their relationship public; Johnathon and Josh married in September of 2011, the same month that the repeal was enacted.

“DADT was the only reason we hadn’t been married earlier,” Josh explained. Though civil unions were available while the couple was living in Hawaii, “we didn’t want a civil marriage,” Josh said. “We wanted to be married.”

With no more legal baggage to worry about, the newlyweds began looking around for an adoption agency. There was one local agency in Hawaii that was eager to work with them, but the agency was new to domestic adoptions, having specialized until recently only in those originating internationally.

“We used them for our home study,” Josh said. “And they kept calling and leaving messages, asking us to consider using them for the adoption, too.”

But Johnathon and Josh had both read Dan Savage’s book “Kid” and liked what they’d read about the agency he’d used in Oregon to adopt his son, D.J. So they began working with that agency, and were eventually matched with a woman in Oregon, who was in the process of getting a divorce from her husband.

“Our profiles and personalities matched well,” Josh said. “We met her, and it seemed like it would be a good match.” The couple was still living in Hawaii when she went into labor, but they managed to make it to Oregon in time for the birth. “We made it for the delivery,” Josh said. “And even cut the cord.”

But as happens all too often with adoption processes that allow birth parents to back out of an adoption agreement for several months after the birth of a child, this situation didn’t work out for Johnathon and Josh.

“The birth mom decided to parent,” Josh explained. “She had a change of heart after delivery, so she decided not to sign the paper relinquishing her parental rights.”

When Johnathon and Josh returned home to Hawaii, alone and frustrated, all of the messages left on their machine from the local adoption agency started to seem more attractive. Sure, they were newer to the game, but why not give them a shot?

“Eventually, we returned their calls,” Josh said, and it’s a good thing they did: Not even two months later they welcomed their daughter, Kylie, into their home.

A Gay Dad, Deployed

Given the nature of their jobs, Johnathon and Josh are no strangers to moving. From Fort Lewis, Washington, the couple moved to Fort Wainwright, Alaska, in 2002, where they spent two years. Afterwards, they found themselves in San Antonio, Texas, for three years. Then, starting in 2007, they had an 8-year stint in Hawaii, which is right about the time I started to lose sympathy for their experiences with relocating so frequently.

But just this year, a few months before our interview, the couple moved back to San Antonio, where both took up work at the San Antonio Military Medical Center, Josh as the residency program director for internal medicine at the San Antonio Uniformed Services Health Education Consortium and Johnathon as a staff registered nurse in the gastroenterology clinic.

The couple has also spent significant time apart during this time, whenever Josh is deployed abroad. In 2009, before they had welcomed Kylie into their home, for instance, Josh was deployed to Iraq, while Johnathon stayed put in Hawaii.

That experience was difficult for both of them. But now? Johnathon and Josh are dads. So when Josh received notice of his deployment to Djibouti last year, when Kylie was just a year old, they knew it would be much more challenging this time around.

Josh worried that his year-old Kylie was going to be a completely different person when he next saw her. “So much happens at that age,” Josh lamented. “She went from crawling when I first left to walking and talking all while I was gone.”

It helped that Josh was able to talk to Johnathon and Kylie often. “I was fortunate that where I was in Djibouti we could have frequent contact,” Johnathon said. “We FaceTimed almost every day. Kylie seemed to take to that pretty well.”

Still, it could get lonely for Josh living abroad, and he grew frustrated during times he couldn’t reach his family. “Sometimes I’d be missing Kylie and wanting to talk to her, but I couldn’t because of the time difference. Or sometimes [Johnathon and Kylie] were off doing something,” he said. “I’d try to be understanding, but sometimes it’d happen a couple days in a row. There wasn’t anything to do about it, because Johnathon needed to have his life.”

Even though Josh spoke with Kylie almost daily, he worried she might not know who he was when he returned the next year. “But she actually took to me pretty well when I got back,” Josh said. “And truthfully,” he continued diplomatically, “the deployment was all much harder on Johnathon than on me.”

Johnathon, of course, was left to care for Kylie alone. “We had some friends nearby, but no family,” he said. In addition to his duties as dad, Johnathon had a couple of other things going on his life: He was working full-time while also attending graduate school. And, just to complicate his life further, he was also overseeing a major home renovation.

“It was tough,” Johnathon conceded, understatedly. And right before Josh’s deployment, he had an epiphany: It was going to be too tough to do all of this alone. Something would need to give.

“I was working on a paper for school, and could hear Josh in the background playing with Kylie, keeping her happy, and it suddenly hit me,” Johnathon said. “Once ‘Other Dad’ is gone, doing all of this at the same time is going to be impossible.” He started to do the math – Johnathon was working as the head nurse of five separate clinics until 4 p.m. each day, and then would immediately start his schoolwork. When would he have time to parent?

“I just realized, I’m not going to have time with my child if I keep this up,” Johnathon said. Soon after, he dropped out of school. Clearly, Johnathon did what he had to given the circumstances, but did any part of him resent having to give up on school?

“No,” he said quickly. “I’m glad I did. I was gung-ho about school at first, but now that I have my daughter I’m not anymore. Kylie is going to remember me as being there for her, not for having a master’s degree.”

Josh returned from Djibouti just a couple months ago, and fortunately, for the time being, the family is intact again. But the family didn’t have much time to celebrate their reunion. “As soon as I got back, we went straight into ready to move mode,” Josh said of their move from Hawaii to San Antonio. “My whole life has been in transition for a year and a half now, so I’m just looking forward to having permanent housing, having a real home, for the first time in a long while.”

And so how was Kylie taking to having “Other Dad” back?

“Three months he’s been back,” Johnathon said, “and you wouldn’t know anything different. She’s integrated very well.”

But isn’t it likely that Josh will have to deploy again? Do the dads expect it to be harder on her to lose “Other Dad” when she’s older enough to understand what’s happening?

“I hope I won’t have to deploy again for a while,” Josh said, but he acknowledged he probably will deploy again at some point in his career. He’s not, however, overly worried about her. “When we were moving, I was worried [Kylie would] be upset that all her stuff was gone when we packed her room up, so I gave her a pep talk,” Josh said, noting that moves are often difficult for young children. “I thought she’d cry and have a hard time with it. But she just kind of looked at her room, looked at me, and said, ‘Okay.'”

“She’s a tough kid,” he added, simply.

Life under DADT

Mid interview, I changed course with Josh and Johnathon because it suddenly dawned on me that I hadn’t asked a very simple question: how did they both find themselves in the military in the first place? As gay men, living under DADT, didn’t they know they were signing up for a lifetime of secrecy in a discriminatory institution?

When Josh first joined the military, he didn’t think much about the difficulties of serving under “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell” for one very simple reason: He didn’t realize it would affect him when he first signed up. “I didn’t accept the fact that I as gay until I was in medical school and on a scholarship,” he explained. “I was about 24 when I finally decided to accept that part of myself. Then I didn’t know what to do. I had already made the commitment to medical school.”

Josh always knew he wanted to go to medical school, and figured joining the military would be an affordable path to becoming a doctor. And it probably didn’t hurt that he’d be furthering the family’s military legacy: Both his father and grandfather were service members as well.

After enlisting and coming to terms with his sexuality, Josh says he never found serving under DADT overly burdensome.

“As a medical officer, we had it a little bit easier than other lines of work in the military,” he explained. “The medical side has always been a little bit more welcoming of LGBT people. So I didn’t have any major issues.” That said, every time Josh was assigned somewhere new – which was often – he’d have to go back into the closet until he felt comfortable in his new assignment, particularly when his assignment was abroad.

“I just had to feel things out initially, like when I was deployed to Iraq in 2009,” Josh said, pausing a moment. “I just had to be more careful,” he said, without elaborating.

Unlike Josh, Johnathon, who is originally from Australia, did not come from a military family.

“But as early as year 10,” which would translate to “Sophomore Year” in the United States, “I always knew I was Navy-bound,” he said. Johnathon started as a cadet in Australia, but in 1986, during naval reserve training, he came down with a severe case of meningitis and encephalitis, which is caused by a virus that results in the inflammation of the brain. He was hospitalized for 6 months.

“I missed a good chunk of school as a result,” Johnathon said, “which meant I couldn’t go into the naval academy.” So instead, he decided to become a nurse. Originally, he had plans to go to the United States after receiving his degree, work for a year, and then head back to Australia to join the Navy. But then he met Josh, “and ended up staying in America for 22 years,” he said, laughing. He originally hoped to join the United States Navy as a nurse, but they wouldn’t accept his degree, so he instead joined the Navy Reserve for 8 years.

“I very much enjoyed my experience in the Navy Reserve,” Johnathon said, “but it was pretty homophobic,” mentioning there was a lot of anti-gay slander and joking occurring among his fellow male sailors.

“There was an encouragement of watching porn by certain members from their laptops in a group environment,” he continued. “It was almost encouraged for comments to be made. If you didn’t show an interest it was asked, ‘What, are you gay?'” (Watching porn with other men sounded pretty gay to me, but what do I know?)

Josh says he faced less overt forms of homophobia, apart from this one rather terrifying experience: During his first two years of active duty, when he was stationed in Fort Lewis, Josh received an anonymous envelope in his mailbox at work. He opened the letter to find a picture of him staring back at him, and immediately recognized it as one he had posted on an online dating site.

“I guess they saw the ad online, and were threatening to out me,” Josh said. Though he didn’t think that much of it at the time, he received a similar letter a week later. And then another one the week after that.

Now, if I were to receive a threatening anonymous letter that so much as insulted my choice of shoes, I’d report it to the Secret Service, hire a handsome bodyguard, booby-trap the entrance to my apartment, and generally make sure everyone around me knew how much danger I was in. But Josh didn’t have this luxury. Should he report the letters to his higher-ups and risk outing himself, with possible discharge under DADT? Or should he do nothing, and allow the letters to continue, unabated? Eventually, as the letters grew increasingly belligerent, he decided he needed to say something about it.

“I showed them to my boss and just said, ‘Look, I’ve been getting these messages,'” Josh explained. His boss never asked if Josh was gay, and Josh never told. “She just said, ‘Well, this is criminal behavior,’ and she took them to the JAG,” he said, using the acronym for the Judge Advocate General’s Corps, the legal arm of the United States Army. But then, just as suddenly as they had started, the letters stopped. “I still don’t know who was doing it,” Josh said.

Apart from that experience, which Josh speaks about with remarkable calm, DADT had bigger, day-to-day implications for he and Johnathon as a couple. Under DADT, for instance, Johnathon wasn’t eligible to receive the financial and legal support that was available to straight spouses. He didn’t receive the same dependent pay that other couples receive. He couldn’t be listed on Josh’s health insurance. He couldn’t benefit from the spousal hiring preference policy employed by the army, and had to compete against the general population for a job. The list goes on.

“None of it was that major,” Josh said. “It was just a ton of little small issues that added up to big trouble.”

And Now… An Army of One?

So what has changed for the family, now that DADT has fallen? Has discrimination, against LGBT military families, de facto and otherwise, fallen by the wayside as well?

Josh, who just got back from his first yearlong deployment since DADT was repealed, has noticed a marked improvement. “In Djibouti it was a joint task force environment, so we had the Army, Air Force, Marines and Navy. I was very open and out. I didn’t encounter anything overt from anybody.”

That’s not to say, however, that LGBT military families are treated completely equally. LGBT service members, Josh said, are still treated differently in some ways than their straight counterparts. For instance, while straight families often have access to reproductive medical care, that assistance is not always available to LGBT families. And even when assistance is available, it’s often not evenly applied.

“One of the things I see discussed a lot on the Facebook groups that cater to gay military families is reproductive medical care,” Josh explained. “There seems to be a lot of variability, especially between gay men and lesbian couples, for who can get reproductive assistance.” Some lesbian couples, though certainly not all, are able to get assistance with in vitro fertilization (IVF) in military facilities. Gay male couples in the same units most often can’t. “There isn’t any assistance at all for gay [male] couples,” Josh explained. “And it’s just a gray area whether they’ll provide infertility services for women.”

Additionally, even though the United States military is no longer allowed to treat LGBT service members any differently than straight ones under the law, LGBT service members can face legal discrimination abroad.

“If I were assigned to Germany right now,” Josh said by way of example, “Johnathon wouldn’t be able to come with me. Germany hasn’t updated their SOFA agreement yet,” he continued, using the acronym for status of forces agreements, which are negotiated terms between two nations that detail how militaries will serve within each other’s borders.

Really? Though same-sex marriage is not yet legal in Germany, I still found this quite surprising. What does Germany have to gain by denying the right of LGBT service members to bring their families on deployment?

“It’s mostly politics,” Josh explained. “You don’t get something for nothing. We say we want the families of our gay service members to come stay in your country, and the other country will say, okay, but only if we address this other issue that we care about.” As a result, while foreign governments are busy playing politics, Josh may be put in the predicament of choosing between doing what’s best for his family, by only requesting deployment in countries where he can bring Johnathon and Kylie along, or his career.

***

Though much progress has been made in the post-DADT era, clearly not everything is perfectly equitable for LGBT service members and their families. But as I was wrapping up our call, Josh interrupted me quickly. Perhaps worried he would leave me with too negative an impression of life for LGBT families in the military, he added this last thought:

“I’d just like to reiterate that, today, the military has a lot of great career opportunities whether you’re gay or straight.” Josh said. “It’s a great time for people who had said they wouldn’t join to consider doing so. And soon, even transgender individuals have career option they didn’t have before,” he continued, in reference to the Pentagon’s announcement this past July that it will allow transgender individuals to serve openly, beginning next year.

Despite some residual impacts here and there from the DADT days, “I’d say we have a very gay-friendly military now,” Josh said. He offered a story by way of example.

This past June, on the same day the Supreme Court found for a nationwide right to same-sex marriage, Josh was sitting in a military event headlined by General Tammy Smith, an out lesbian and co-founder of the Military Partners and Families Coalition, which caters to the needs of LGBT military families.

As it happened, the marriage decision came down in the middle of General Smith’s speech. And when it did, General Smith’s wife stood up and interrupted her speech, saying, “We just got nationwide marriage equality!”

“It was great because there were all sort of people in the room, it wasn’t just gay people,” Josh said. “There were lots of straight service members, too.” Yet everyone, gay and straight, stood up to applaud the announcement.

“It was a great feeling,” Josh said.