Things were different for Brian Rosenberg and Ferd van Gameren, who were already in their forties by the time they began thinking about having kids. Their early years together focused on keeping Brian, who is HIV-positive, healthy and Ferd negative. But once protease inhibitors emerged and Brian’s health was stable, the couple decided to focus on enjoying life. They moved from Boston into a one-bedroom Chelsea co-op in New York City, started summering in Fire Island, and hopped around their friends’ parties having “a gay old time,” as Brian put it.

Dr. Ann Kiessling

Dr. Ann Kiessling

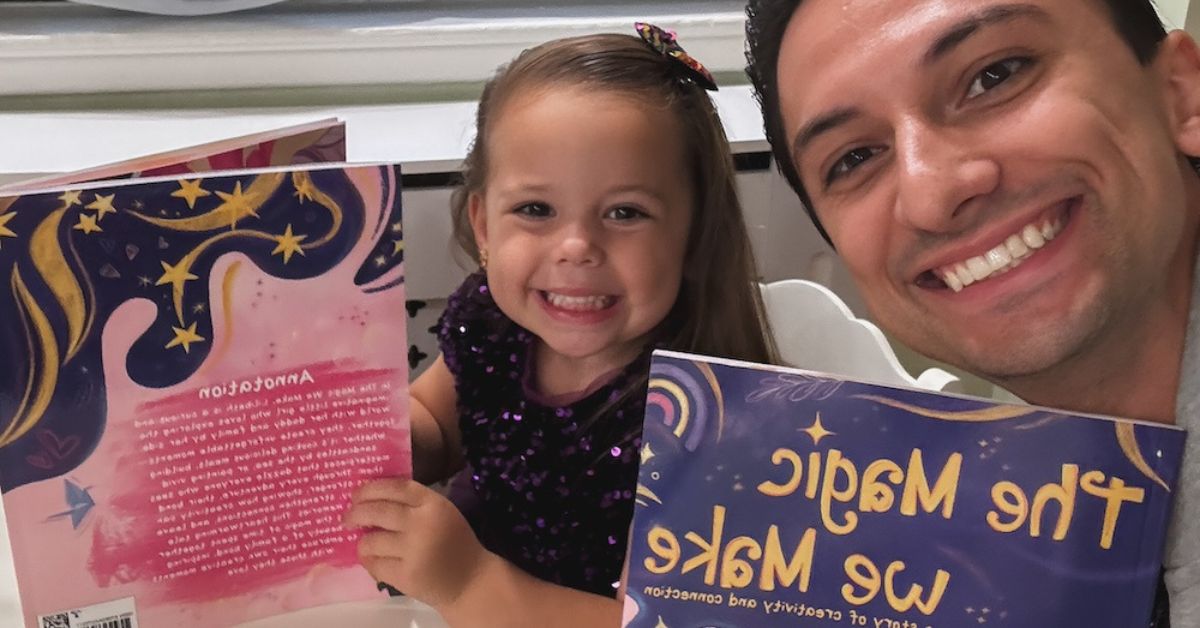

After several years, though, all that began to pale. “We started thinking that life had to be more meaningful for us than the next party, the next fabulous vacation.” They wanted a family, and all the responsibility, love, and exhaustion that went with it. They tried adoption first, but when one birthmother backed away, their hearts were broken–so they discussed surrogacy. Given his HIV status, Brian assumed that Ferd would be the biological dad–but Ferd wanted to raise Brian’s bio children. And so in 2009 Ferd went online and found the Special Program for Assisted Reproduction, or SPAR, dedicated to helping HIV-positive men father children safely. The program is run by the Bedford Research Foundation and its director Dr. Ann Kiessling.

Back in southern Europe, by 2011, Aslan was learning about the same option. He was seven months into a new relationship that seemed as if it would stick—and despite himself, he began to imagine having a family with this man. Coincidentally, an American friend forwarded him an article about Circle Surrogacy, which worked with HIV-positive gay men in the States. “And it gave me, like, a wow, big hope, a new window to plan my life again!” Aslan quickly contacted Circle Surrogacy, which connected him with Dr. Ann Kiessling. “She was very kind and explained all the procedures, that it’s completely safe. And this was the start.”

But how can HIV-positive men father children?

“How” has both a practical and a technical answer. This article will tell you the practical steps to take, one by one, with some technical information mixed in along the way. Experts agree that it can be done safely. According to Dr. Brian Berger of Boston IVF, over the past 15 years fertility centers have helped conceive thousands2 of babies fathered by HIV-positive men—and not a single woman or child has been infected as a result.

So how can an HIV-positive gay man become a biological father? Let’s look at the process, step by step.That’s because, apparently, HIV cannot attach to or infect spermatozoa—the single-cell swimmers that deliver chromosomes to an egg. Sometimes the surrounding fluid—the semen, the ejaculate that carries the sperm along, and which is made separately—does include HIV. But sperm is made only in the testes, which are walled off from the rest of the body, heavily fortified against the illnesses or infections that might affect the rest of the body, for obvious evolutionary reasons. Because sperm doesn’t get mixed with semen until the very last moment, at ejaculation, it remains safe. And after decades of research, the medical profession has figured out how to use only the uninfected sperm to fertilize an egg.

Step 1: Make sure dad is healthy.

The first, and most important, step is to ensure that the prospective dad is healthy—that his HIV levels are undetectable or nearly so, his T-cell count is high, he’s free of other complications or infections, and he is working closely with a doctor to stay in good health. Says Dr. Bisher Akil, a New York City physician who specializes in caring for HIV-positive patients, “Can an HIV-positive gay man become a parent? The answer in 2014 is absolutely yes.” In 2014, no one should use his HIV infection to stop from having a full and normal life, he emphasizes. “The only point I make to potential fathers is that they need to take care of themselves and make sure they have their infection under control. The occasional medical problem that might appear, whether or not related to HIV, needs to be treated very aggressively. They need to be compliant with medications and treatment. That’s not any different from any father with a chronic illness. Now that they have responsibility of having a child, we want to take them through their lives.”

Dr. Akil says that to go forward with insemination, an HIV-patient must have had undetectable virus levels for 24 weeks, and a minimum T-cell count of 200 cells per millileter of blood. Restoring the immune system as measured by T-cell count, says Dr. Akil, takes three times as long as reducing levels of the virus. If the prospective father hasn’t been taking care of himself, reaching this could take a couple of years. It can take weeks or months to get the medication dosage just right. Then, after six months of undetectable virus levels, it might take another 12 to 18 months for the immune system to stabilize.

Both Brian and Aslan had been committed to their treatment regimens, so they were immediately ready to move on to the next steps. Although we’ve numbered these for convenience, these steps aren’t necessarily in chronological order.

Step 2: Make sure the sperm is safe.

Brian and Ferd started by meeting with Dr. Ann Kiessling, an award-winning reproductive biologist who has researched HIV and reproduction for thirty years, much of that time while on Harvard’s faculty. Kiessling starts by talking to the men involved to be sure that they’re taking their health and parenthood seriously “and this isn’t just some kind of a lark. That they’re in the care of an infectious disease person. That they’re being safe and taking their medicine, they’re taking care of themselves.” After that conversation, the prospective HIV-positive father delivers at least two semen samples (i.e., each independent ejaculation). Bedford Labs washes and cryopreserves half of each one, and tests its other half for HIV.

Here’s what Kiessling has found since the emergence of the protease inhibitors: Of the semen samples she’s tested from HIV-positive men with no detectable viral load, roughly 15 to 18 percent contain some HIV. That means that 85 percent of a man’s semen samples have no detectable virus whatsoever. If a particular sample tests positive, Bedford Labs discards its matching half (safely, of course). But if it tests negative, Bedford Labs sends it on to the fertility center to meet its future life partner. (More details at https://sementesting.org/).

But Dr. Kiessling’s testing, while essential back in the earliest days of HIV-positive fathering, is now an unnecessary precaution, says Dr. Brian Berger, director of Boston IVF’s Donor Egg and Gestational Carrier program. Dr. Berger said that today’s accepted standard of care, as issued by the ASRM (American Society for Reproductive Medicine), is simply to wash the sperm with the advanced techniques now in use. Just as the sperm washing gets rid of the other infections and bacteria that might be in the semen, it appears to clean off HIV particles, so long as the prospective father has an undetectable viral load. Just to be safe, Boston IVF’s precaution is to select a single washed sperm and, using a glass needle, inject it directly into a single ovum – never directly into a uterus, always in vitro – in a procedure called ICSI, or intra-cytoplasmic sperm injection (pronounced “ICKS-ee”).

Berger explained, “We’re not taking about using millions of cells, we’re taking one single cell. And this is a sperm cell that has been washed, that has no semen associated with it, no other fluid. In theory, the chances of transmitting HIV in the lab with a single washed cell, of HIV infecting the developing embryo, and of that infected embryo being capable of infecting a women’s uterus–we think that risk is, if not nil, then one in billions or at least millions.” After thousands of pregnancies at fertility centers around the country over the past decade, Berger said, “there’s never been a single case ever reported where a single sperm injected into an egg (ICSI) has resulted in viral transmission into any woman, or the baby for that matter.” He has no objection to working with Kiessling’s lab whenever he’s asked; surrogacy programs in particular, he says, sometimes use her lab, which he believes may be for psychologically or liability purposes.

Once you’ve got the sperm clean and available, you need the additional parts.

Step 3: Locate an egg donor and gestational carrier.

Once upon a time, a surrogate mother donated both her egg and nine months in her uterus. That sometimes led to legal and emotional difficulties. Now you select an egg donor and gestational carrier; work with a fertility center to get the two women on the same cycle; have the fertility specialists safely inseminate several eggs in the hope that one or more will conceive and develop into embryos; and implant a viable embryo or two in a gestational carrier, or surrogate, who carries the pregnancy to term.

Boston IVF was the fertility clinic that Brian and Ferd used to put all the elements together. Boston IVF offers a bank of potential egg donors, carefully screened for genetic, medical, and psychological characteristics . Brian and Ferd, however, went through Circle Surrogacy to find both their egg donor and their carrier.

But there are a couple of particular steps you will face specifically because you are HIV-positive. First: will you tell the egg donor? And second: you must tell the gestational carrier, to ensure informed consent. Depending on the route you pick, the agency, lab, or center you are working with will have its own protocol for how to go forward, but the general outline of what happens is the same.

Egg donor.

When it comes to choosing an egg donor, everyone’s interests are slightly different. Some want a donor with the same physical traits as the nonbio dad. Circle Surrogacy’s founder, owner, and attorney John Weltman says he was one of the very first gay men to become a father via surrogacy, 20 years ago; he now specializes in helping gay men and HIV-positive men become dads. Weltman says that what people seek in an egg donor “varies enormously. One woman wanted a happy gene. Another wanted someone who’s healthy. You might think you care about looks, but once you read a particular donor’s portfolio, you are very taken by her personality.”

Circle asks whether women would be willing to be known, and whether they’d be willing to donate to someone HIV-positive. Weltman also encourages clients to meet the donors, without last names or contact information, and to disclose HIV status, so that any future child who does meet the egg donor doesn’t have the burden of keeping that status secret.

Brian and Ferd looked at Circle’s several hundred profiles of young women 21-29 with carefully screened histories, seeking a sweet and creative woman willing to being known, someday, by the child. When Brian and Ferd met “Karen,” they knew she was the one, Brian said. “She was so incredibly cute, sweet, nice, and funny. It’s a very awkward situation, meeting someone who’s going to give you her egg, and yet somehow it wasn’t uncomfortable. We left that meeting knowing: Karen was it.” They let her know about Brian’s HIV status, feeling that that was only right, and have since stayed loosely in touch by email.

Gestational carrier.

Then comes choosing the woman who will carry the developing embryo during gestation. Circle Surrogacy has relationships with about 40 potential surrogates at any given time, says Weltman, some of whom have agreed in advance to consider carrying a child for HIV-positive men. Circle offers prospective parents the choice of carrier who is most likely to be coming available, and whose legal situation and personality they believe will work best. If the intended parents are interested, he sends a file about those future parents to the surrogate, so that she can decide whether she’s interested in meeting them. If they meet and get along, everyone moves to the next step.

Why meet the surrogate? While the choice of egg donor has larger long-term implications, Weltman explains, the gestational carrier is the person with whom the prospective dads are more likely to develop a close relationship. “She will be in your life for a year. She carries your child,” Weltman says. “When the child first asks, ‘Where’s my mommy?’ most [gay men] point to the surrogate, the birth mother. When the child gets older, maybe 7 or 9, and starts understanding genetics, then the donor becomes more important.”

For those who go through the SPAR process, Dr. Kiessling insists on speaking to the surrogate herself. A gestational carrier has only signed up for pregnancy , not for every medical risk that a wife or girlfriend might be willing to take by carrying the child of someone they love. Since a carrier is trusting others with her life, Kiessling wants to be sure she knows exactly what she’s getting into. “I don’t want any of the surrogates told that there’s no risk to do this,” she said. “I want the surrogates to know what we know.” Here’s what Kiessling tells them: Between the program’s founding and 2013, of the HIV-positive men whose sperm Bedford Labs has worked with to date, 163 women have given birth to 189 children—and not a single woman or child was infected. That, however, doesn’t mean there’s no risk. As she explained, “The statisticians tell me that they can’t calculate a risk factor until we get to 400 babies.” If there are still no infections at that point she’ll be far more confident that the method is truly safe.

At this point, Ferd and Brian considered using both of their sperm, but it turned out that Ferd would have needed surgery to be fertile. He chose not to do it, especially once Brian’s samples made it through the screening. And here’s where their story gets interesting. On a Friday afternoon, they put down the “sizable” deposit with Circle , and went off to Fire Island for Memorial Day weekend. On Tuesday morning, still hung over, they got a call from their adoption agency—which, unbeknownst to them, had bumped them to the front of the line after their previous adoption possibility had fallen through. A baby had been born in Brooklyn. Did they want him?

The answer was easy: Of course! Within two days, Brian and Ferd were exhausted, delighted fathers of a newborn.

But they didn’t want him to be a singleton. And they had already plunked down that huge nonrefundable deposit. Why wait? And so—in the midst of moving to Toronto with an infant, because Ferd’s U.S. visa had expired and DOMA hadn’t yet been knocked down–they went ahead with meeting Andrea, a carrier in West Virginia, who preferred working with gay men because there was no woman involved to be jealous that Andrea could do what she could not. The two couples—Andrea and her husband, Ferd and Brian—got along fine. They gave the okay.

Step 4: Have a fertility center mix the parts.

Brian and Ferd worked through Boston IVF’s Dr. Berger, whose lab used Brian’s washed, SPAR-selected sperm, and used the ICSI process, with a single sperm cell per ovum, to fertilize the eggs. The result was several “Grade A embryos,” as Brian put it. Having heard from friends whose embryos had failed to develop, the two men and Andrea agreed to Dr. Berger’s suggestion that they implant two embryos, just to be on the safe side . According to Brian, Dr. Berger told them that at that time, if one embryo was implanted, chances of a child were about 15 percent; if two, chances were closer to 40 or 50 percent. (Berger says that Boston IVF has been steadily increasing its success rates, and that one five-day-old blastocyst now has about a 40 percent chance of developing.) The day after the implantation, Andrea told them she was pregnant with twins, as she had been the previous time. She was right.

“Sure enough, at 35 weeks and one day, we got a call,” said Brian. Afraid to put premature newborns on a plane, the two men packed a car and drove from Toronto to West Virginia—and drove home a few days later with a pair of baby girls, one three pounds and the other five pounds, colicky, exhausting, and perfect, to meet their big brother—seventeen months older.

Things didn’t go as smoothly for Aslan and his boyfriend Zekai. When Aslan started, the pair had been together for only seven months—and so Aslan decided to proceed as if he would be a solo parent. Although Zekai was completely supportive, Aslan explained, “I thought we had to establish our relationship to be more solid” before thinking of it as a joint endeavor. And so once his sperm was readied, Aslan picked a donor and a surrogate, who both went to Boston IVF, their cycles coordinated, for the implantation.

Nothing developed. Three times. Every cycle failed.

The mountainous expense was beginning to dash his hope for a family. He sat down and calculated his costs: Over two years he had spent $200,000 “between the flights to the states, the contracts, the lawyer, the IVF clinic, the SPAR program, it’s as much as a house. I didn’t know I could raise this sum of money! At this stage, after not succeeding three times, I started to ask myself: What else could I do with all that money?” If he got over his desire to be a dad, he could be well off and travel the world. Was it time to give up?

But Zekai was stubborn, and pushed Aslan to follow his dream. And Circle Surrogacy’s John Weltman found another clinic that agreed to work with Aslan at a lower rate—and another surrogate, Christina3. Somehow, Aslan scraped together the money to try one last time.

Wait, why would a stranger agree to carry an HIV-positive man’s child?

When I spoke with Christina, I had to ask: Why take that risk, however slight? “Because my sister was diagnosed with ovarian cancer when she was nine,” Christina explained over the phone from southern Missouri. “Growing up, I always thought I would carry for her. She decided not to pursue having kids. But after I had mine, I decided to do it for someone else.” Christina, 29, was upbeat and bubbly on the phone, her voice overflowing with happiness at having been able to give someone such an incredible gift. “Some people do it for the money, which is fine,” she said. “A lot of people do it for a friend.”

Christina picked Circle for a variety of reasons. She particularly liked the fact that Circle works with gay men, which meant she could give these men an opportunity they’d never have otherwise. Circle’s application for becoming a carrier gave her pause when she reached the line that asked whether she’d be open to working with someone HIV-positive. After a few days of pondering, she checked yes. “And I’m glad I did.” Being able to give these men a child made her feel profoundly happy to be fulfilling her childhood goal: to bring something good out of her sister’s suffering, to offer normal human happiness to a survivor of a terrible illness.

By this time, Aslan was confident in his relationship with Zekai. And so the two men decided that they would both submit sperm samples. Embryos from each of them developed. Christina agreed to implant one from each. And thirty-five weeks later, the men were the fathers of twins.

Christina says she knew the instant they were born which one was biologically related to whom: one of them slight and dark, one of them taller and fair. Aslan says that they knew which was whose the instant they had seen the ultrasound. Both Christina and Aslan agree that the families have become so close they will surely be vacationing together.

When I spoke with Aslan over Skype, he had three-month-old twins crying in the next room. He hadn’t shaved for several days, he had bags under his eyes, and he was beaming as if he’d won the lottery. At 49, his life’s dream had become reality. “I am smiling, but with black circle around my eyes,” he said, “exhausted and happy.”

“Both our families are so happy,” he said. “The grandmothers are really happy, calling three times a day to see how they’re doing. It’s a new sensation, to be responsible for two little adorable creatures. They are amazing. They are beautiful, like models.”

“We feel blessed,” Aslan said. “We are walking around with our heads up, very proud to be dads.”

[1] Aslan and his partner’s names are pseudonyms to protect their privacy; Aslan’s conservative family does not know his HIV status.

[2] In an email to the reporter dated May 28, 2014, Berger explains how he concluded that the number is in the thousands:

These [see below] are a few of the published articles which discuss cycle numbers and live birth rates. From these four articles alone, there are over 700 babies born to HIV discordant couples. There are of course more articles discussing hundreds more babies in the published literature. Furthermore, the number of babies delivered from clinics such as ours that are treating discordant couples, not part of studies and not published, is probably far higher than those in the published literature. Therefore, the estimate of thousands of babies born from treatment at fertility centers with HIV discordant couples is realistic and possibly conservative.

Semprini AE, Fiore S, Pardi G. Reproductive counselling for HIV-discordant couples. Lancet1997;349:1401–2; 200 pregnancies with no HIV seroconversions from more than 1000 AIH treatments of over 350 women

Vitorino RL, Grinsztejn BG, De Andrade CA et al. Systematic review of the effectiveness and safety of assisted reproduction techniques in couples serodiscordant for human immunodeficiency virus where the man is positive. Fertil. Steril.95(5),1684–1690 (2011). – 1,184 couples and 3,900 cycles, employed IUI (compared with 539 couples and 741 cycles of ICSI–IVF), The median pregnancy rate per cycle of IUI was 18.0% (about 700 babies), range (17.7% to 49.7%) of pregnancy rates per cycle encompassed the ranges described for IVF (130 – 370 babies).

Sauer MV, Wang JG, Douglas NC et al. Providing fertility care to men seropositive for human immunodeficiency virus: reviewing 10 years of experience and 420 consecutive cycles of in vitro fertilization and intracytoplasmic sperm injection. Fertil. Steril.91(6),2455–2460 (2009). The overall clinical pregnancy rate/embryo transfer was 45%; ongoing/delivered pregnancy rate/embryo transfer was 37%. The most frequent obstetric complication was multiple gestation (41%), with 5% experiencing high order multiple (approx 150 babies).

Semprini, A.E., Levi-Setti, P., Bozzo, M., Ravizza, M., Taglioretti, A., Sulpizio, P. et al. Insemination of HIV-negative women with processed semen of HIV-positive partners. Lancet. 1992; 340:1317-1319. Overall a pregnancy rate (PR) and ongoing PR per couple of 45.4% and 36.3% has been achieved with 127 clinical pregnancies, 102 infants born, and 12 pregnancies ongoing with no reported seroconversions.

[3] Christina’s name is also a pseudonym, to protect her privacy in a small Missouri town.