You’re a parent. You want to protect your children from anything bad, ever: fingers in the electric socket, scraped knees, mean kids. You’re especially determined to protect them from the scourge of your own youth: feeling like an outsider. You’re ready to take down anyone who might make your child feel uncomfortable about having gay dads.

And – sorry about this – you’re going to fail.

That’s the message that the first generation of kids who grew up with gay parents has for you: Having a queer dad makes you queer. No, it’s not all better yet. Our children face many of the same discomforts facing gay adults – and they have some special challenges of their own. Of course there’s vastly more acceptance than there was twenty years ago. But different is different. And when you’re a young person, that’s kinda queer.

But here’s the good news: You can help make it a little easier – although not necessarily in the ways you might think.

Some lessons from the children of gay parents

Quite understandably, we couldn’t find families who were willing to let their pre-teens and teens talk on the record, while they’re still sorting out their identities. And so we’ll be hearing mostly from young women who came of age in the first wave of “gayby” boomers – children born to parents who were at least partly out while they grew up – and who have had some time to reflect on their experiences. All of the ones we talked to are trying to make the world better for the gaybies coming of age now – and so the lessons they’re offering aren’t just from their own experiences, but from what they’re hearing from the gaybies of today.

Lesson #1: Don’t make your children keep your secrets.

Dori Kavanagh, born in 1981, is a therapist who specializes in working with children and adults of one or more LGBTQ parents. That passion found her in part because her parents divorced when her mom came out. Her mom lived “in the shadows” with her partner. “We just didn’t want to be ‘The Family’,” she said. They would pass as a heterosexually divorced family, with Dori’s mother’s partner making appearances as a family friend. That put Dori in the closet as well.

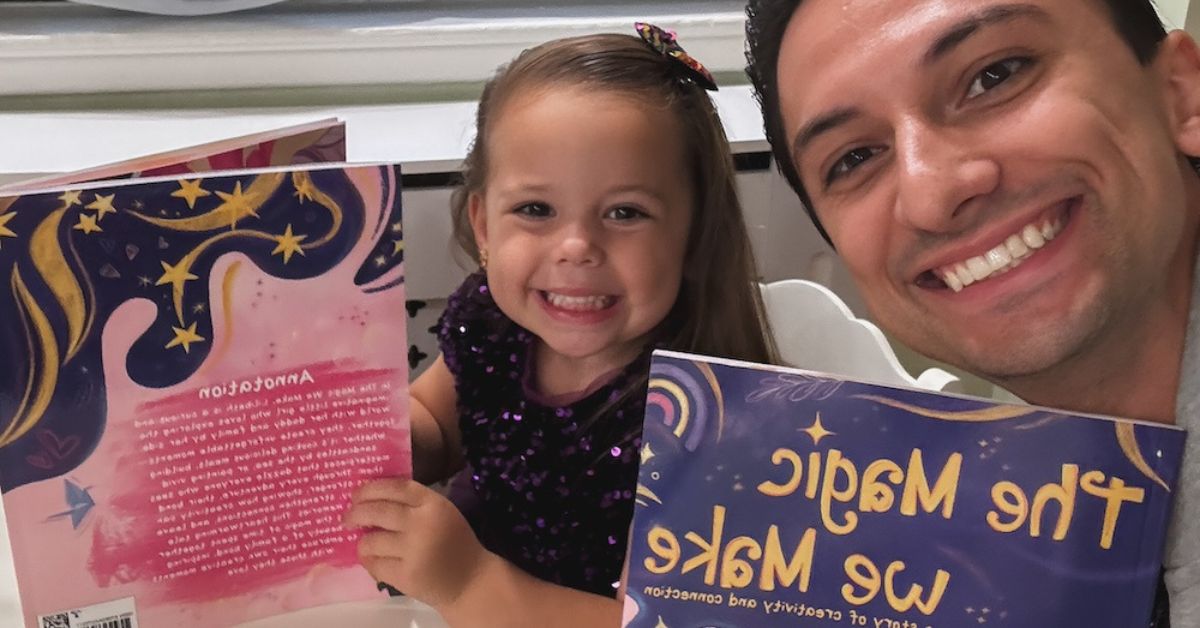

Don’t do that, she urges. Let your children know exactly how they came to be and how wanted they are. Otherwise you are burdening your child with the need to protect you with his or her silence – and that’s exhausting.

That’s certainly how it felt to Jenny Rain, born in 1970 to a heterosexual couple who split up when her dad came out. During the school year, Jenny lived with her mother and stepfather in Peoria, Ill.; during the summers, she lived in Washington, D.C. with her dad and other stepdad. “I really had the best of all worlds,” she says, getting to live with four parents, all of whom coordinated and cared for her.

But the silence was hard. In Illinois, Jenny went to a Catholic school where the nuns prayed for her father to return, causing her mother to roll her eyes. “In the Midwest, you put a smile on your face. That was it. It was very much like a mask because I couldn’t tell anybody that I had a gay dad. You just couldn’t.” That silence was strangling.

Robin Marquis was among the first wave of intentionally conceived children of openly gay folks – and would have appreciated some ability to talk about her family openly and without fear. Born in 1988 to two moms and a gay donor father, whose later partner also became part of her life, she and her brother grew up in a little town in rural New Mexico. Although they lived with their moms, they learned to call their gay donor “dad.” He and his partner behaved like uncles. But for her, Robin says, it was a profoundly important, if complicated, relationship. (More on that later.)

Robin’s moms were semi-closeted. Although everyone knew within their tiny rural town, no one discussed it. The family let strangers think whatever they wanted to think. Silence was as heavy as a stone wall, keeping people out – and for Robin, keeping shame in.

Her moms always told her, “You don’t have to lie. You don’t have to protect us.” But when on the phone with strangers or in doctors’ offices, they used words like partner, and at that time, people didn’t really understand that that meant gay couple. People would either get it, and it was safe. Or if they didn’t, they would think they were business partners, and it was also safe. That was just very subtle and a very real thing that I knew, all the time, was what I was supposed to do.” The “protecting” that she wasn’t supposed to do was to stand up for them or advocate on their behalf. But she kept trying to protect them the way they protected themselves: by keeping their secret, with little white lies and evaded pronouns.

Kavanagh emphasizes that that’s how children learn: not from what you say, but from how you behave. If you pass those secrets on, they get heavier for your children. It’s your job to model how to be comfortable with being gay.

Lesson #2: Let them know they don’t have to protect you from pain.

When your children hear antigay attitudes, they worry about protecting you.

By the time Jenny Rain was in middle school, early in the AIDS crisis, the culture wars were going full blast. She was bewildered by – and afraid of – what she remembers as hate-mongering media portrayals of sex-crazed, half-naked gay men. “It was cognitive dissonance for me because I’m like, My dad is normal. We go to church and brunch on Sundays or we go to the beach for vacation. It was ridiculously normal.”

But children don’t have the defenses that adults have: they are sponges for others’ attitudes. “If there was shaming to be had in society, I took more on than I needed to,” she says. She tells the story of a time when she was 11, and she and her dads were walking on a beach – and teenage boys started yelling antigay slurs. Here’s how she tells it.

“My dads didn’t hear any of it. I was 11 years old, I heard all of it: ‘Fag, queers, sissy!!’ That was the day shame dug its spikes into my heart. I didn’t have words for it and so I just went numb and silent.

“And as we rounded the corner to go back to our hotel, Papi and Dencil noticed that. Dencil could be appropriately sassy at all the right times, and he said, ‘Oh! She’s just having an 11-year-old moment.’ It was actually the perfect thing to say and I didn’t have words around it. I needed for us as a family to just move on.”

That may have been the right response at the time – but wouldn’t it have been even better if the family had an ongoing conversation about how to handle the haters? Neither her mother nor her father had that language in the 1970s and 1980s. In Peoria, Rain says, “We just didn’t talk about it a lot. ‘How do you feel about this? How did this impact your identity? How did this impact who you are?’ Those conversations did not happen.” Even though her father did try, she said, “My dad is of German descent, and so you just…. We just didn’t talk about it a lot at all as a family and that was hard. The silence did not help.”

How anxious was Robin Marquis about keeping her family structure safe and secret? Here’s how much. Except among her parents’ small community of gay- and gay-friendly folks where she could relax and feel at home, she had never heard an adult say “gay” in a positive way – until Ellen DeGeneres decided to come out in her sitcom’s puppy episode in 1997. “I remember crying and like wanting to tell her to not do it because I was really scared for her,” Robin explains. That’s how worried she was about protecting her parents with her silence. She felt the shame being inflicted by the haters – and then felt ashamed of feeling shame.

Annie Van Avery was born in 1978 to a former seminary student and a nun. When she was five, her parents explained to her and her little sister that the family wouldn’t be staying together, because her dad wanted to find “his prince.” That made sense to her: Who wouldn’t want to find his prince? Today, Annie is the executive director of COLAGE – originally abbreviated from Children of Lesbians and Gays Everywhere – which she found in her twenties, and which gave her a profound sense of coming home. She told me the story of “a really wonderful young man” – let’s call him Jonah – with two dads who were, she said, “very open and communicative, just incredible parents.” The dads were constantly vigilant about protecting him from homophobia – talking with the school, clearing the way with other parents.

And so it wasn’t until high school that Jonah let his dads know that, all through middle school, he had been viciously bullied every single day for having gay dads. “They were absolutely stunned by this,” said Annie.

Why hadn’t he told them? Because they were so determined to protect him from hatred. That was their priority. So he wanted to protect them from feeling they had failed, from the pain it would cause them to think that their being gay had hurt him.

The lesson? Let them know that cruelty, discrimination, and bullying happen. Haters gonna hate, and all that. Let them know that most people haven’t really thought about us much, so they’ll pass out forms that say “mother” and “father,” without meaning to exclude. Those moments are painful, but not the end of the world, if you take them as an opportunity to educate. Tell them to come talk with you or some other adult about whatever makes them uncomfortable. And when they do, listen, without judgment. Don’t try to jump in and fix the problem. Let them find their own way through, with your help if they ask.

Lesson #3: They have to come out, too.

When they’re little, you will decide for them who knows and who doesn’t, but as they get older, your children will have to decide whether, when, and to whom they come out as having gay parents, in situations large and small. Give them the room to decide when and how, especially as they get to middle school and beyond. Sometimes it’s worth the emotional cost to have the conversation; sometimes it’s not. That’s their decision. How they do that will depend in part on what you’ve modeled and in part on their sense of the risks and rewards.

When Robin Marquis got to high school, her moms would take her to a larger town 45 minutes away for her extracurriculars. There she did what we all know so well: She elided or changed pronouns when talking about her non-bio mom. Or sometimes she invented a “dad,” a mash-up of her other mom and her dad. (How many times did you say “they” instead of “he” or pretend your boyfriend was a girlfriend?)

What helped was pop culture. Although Ellen lost her show (at the time – we know now that the story turned out well!), the floodgates had opened. Gay people were pouring out on TV. One day Robin’s best friend from birth – who knew her parents but with whom the family structure had never explicitly been discussed – mentioned that she loved the show “Will & Grace.” Robin was overwhelmed with relief: The friend was okay with her gay family.

That doesn’t mean Robin yet had the nerve to out herself at the high school. She hated hearing the antigay bullying all around her: the putdowns, the teasing, “that’s so gay,” the “eeew” when two boys accidentally brushed up against each other. But when she went to her high school’s Gay-Straight Alliance, she says, the other kids looked at her as if thinking, “Who is this straight girl, and why is she here?” The internal stone wall insisting that she protect her parents’ secret at all costs was unbreachable. Since she couldn’t explain, she stopped going.

Robin still remembers the first time she voluntarily and directly said that her parents were gay. She’d finished college, and was living in a queer anarchist commune in Spain – which was the place she first heard anyone use the term “queer,” using it as a term more expansive than just sexual orientation. So she said she, too, was queer, “like, ‘Well, actually, like I grew up in a gay family.’” She felt the sensation of an immovable, rocky wall come up between her life and her words as the conversation veered toward her family – “and then I stepped over it. It was a moment I will absolutely never forget.”

For Jenny Rain, coming out happened in fits and starts. It began when she wrote a biographical story for a college class called “My Little Secret.” Her instructor called her in to the office on the pretext of helping her with the writing – but “she basically drew the story out of me.” Telling that story was revelatory: it was her story. Not her dads’ story. Not her parents’ story. Hers. Claiming that “was the single most powerful, validating moment,” she says with the enthusiasm of a convert. “For me, the value and healing came from telling my own story.”

But that first toe in the water wasn’t yet a full plunge. Faith had always been a large part of Jenny Rain’s life, whether she was in Peoria or in D.C., where she and her dads attended Dignity services. The tug toward faith increased as she got older and came into her own, so strongly that she went to seminary. Her Christian circles were infinitely welcoming about almost everything: she could say her parents were divorced, that she struggled with one issue or another, and she was flooded with warmth. But the minute she mentioned her gay dads, “it was like their jaws would drop. I wasn’t rejected but it was almost as if people would take a step back from me.” She learned to keep it to herself.

Until finally Jenny decided that she could no longer do it; if someone wasn’t going to accept her family, that was someone she didn’t want in her life.” Now she puts a photo of herself with her dads on her desk, for anyone to ask about or see. Claiming that identity openly has given her a new sense of freedom. Rain has now taken as her mission to make churches more welcoming to the rainbow family, and is working on a book called “Will They Laugh if I Call You Daddy? Growing Up with Two Dads in an Evangelical World.”

Lesson #4: Talk with your children about your family structure.

Sometimes our new family models seem creative to us – but can be opaque to our children. If yours is unusual, keep up an ongoing, age-appropriate conversation about that difference.

In high school, Robin struggled with the fact that she and her brother had grown up calling their semi-attached donor a “dad.” If he was a dad, like other kids’ dads, why didn’t they see him every day? “He was around on important dates and once a year we would have camping trips, just alone-time together,” she says. But her model of fatherhood was what she saw in others’ families. She felt abandoned rather than loved.

Looking back, she says, she realizes that her parents were trying to create another model beyond the nuclear family while using the same terms. But they never communicated that to her – and the term “dad” was just too powerful to tweak without explanation. For a few years, she was so angry about his distance that they just didn’t speak at all.

Lesson #4b: Dads, pay special attention to your daughters

Worse, since her father remained close with her brother, Robin Marquis worried that he didn’t like her because he was gay and liked boys – and she was a girl. “I think that was internalized homophobia,” she says now.

But she wasn’t alone in that hunch. Gay dads with daughters should be prepared for a possible moment in middle or high school when your little girl wonders if, since you love men, you can’t really love her. A writer on the COLAGE website, who identifies herself as age 19, wrote that when she was 15 she had feared that her dads couldn’t love her as much as they said they did, because they loved men and she was a girl – but now knew she had the best parents in the world.

Lesson #5: Meet up with other gay- and lesbian-headed families.

We all need a community of others like us, people with whom we don’t have to explain ourselves. Remember how freeing it felt to make your first gay friends? Our children need the same, and maybe even more so. The kids don’t have to sit down and talk about having gay parents; it’s comforting just to know that that doesn’t have to be explained.

How you do that is up to you. You can find nearby families online and meet up informally at the playground. You can go to Family Week in Provincetown. Maybe you’ll move to a neighborhood specifically because there are plenty of other queer families around. Just don’t let your child be the only one he or she knows.

Says Robin Marquis, who is now the COLAGE program director, “I have never met someone in the years and years and years I’ve been doing this work that did not remember the first time they met that other person like them, who also had gay parents.” Being able to relax without having to translate is something all humans need. “It’s a very big part of how they learn to see themselves and how they are able to form their own self-worth.”

Lesson #6: Take the burden off your children to prove that your family is okay.

Getting together with other gay-headed families helps relieve your children of the unspoken pressure to prove that they are turning out fine, thank you! Robin Marquis explains that one of the common issues for “for folks with LGBTQ families is the need to protect your parents from any sign that they are not the best parent.” They know gay families are under attack – and that their healthy adjustment and well-being is Exhibit A in whether gay people should raise kids. For herself, Robin says, “it took a really long time to be honest with people and to share that there were things that are hard.” Make sure they know it’s not a betrayal to talk about their frustrations and anger, just like any other kids.

Jenny Rain tells the story of visiting “dear friends,” a female couple, living in Alabama with a middle-school-aged son. “I was able to pull their son aside so he had a chance to talk with me, and he asked me a round of questions. ‘When you were growing up, were you ever, like, embarrassed by your dad? Did you ever feel this, did you ever feel that?’” When Rain assured him that yes, indeed, she had felt embarrassed and ashamed, he pushed further. “ ‘Were you ever embarrassed, like, when your dads held hands?’ ” Having had the experience of both a heterosexual and a gay pair of parents, Rain was able to reassure him that every child feels embarrassed when his parents show affection – it wasn’t a gay thing, it was a parent thing.

As one COLAGE kid named Kelsey wrote on the KidSafe blog about an encounter where she tried to prove to someone how brilliantly she had turned out, and decided she didn’t have to do that any more. “Over the years, I have learned that other people’s opinions of your family don’t make a difference if you don’t let them hurt you. There is no need to overcompensate. We COLAGERS already know how great your family is.”

Lesson #7: Be ready to have them queer our identities.

However you conceive of your gay identity, be ready to have it challenged by your children, someday. That’s been Robin’s role in her family. Once she felt free to “come out” as having gay parents, her other feelings started to flow more freely – and she started to realize that she, too, was attracted to women. When she returned from Spain, she began announcing that she was queer.

But since she presented as generally feminine and had had boyfriends in high school, the reaction was denial. Her friends thought she was just trying to be shocking. Still more stunning, one of her moms said, “ ‘Don’t go be one of those straight girls that breaks gay girls’ hearts.’ I was 19, and both of my moms didn’t start dating women until they were in their twenties!” It was a breathtakingly insulting rejection, an alienating experience of being “othered” by her own family.

“We call ourselves second generation,” Robin says, explaining that often it’s harder for the children of gay parents to come out themselves than it is for kids in straight families. That’s true partly because of the pressure to prove that gay parents have “normal” kids (see Lesson #6, above).

And it’s partly because their identities don’t necessarily match up with their parents’. The new generation defines themselves differently than we once did, paying less attention to one fixed definition of who they love and closer attention to where they might belong on a spectrum of gender and attraction. Robin, for instance, dates people of all genders and sexualities, she says; for the past seven years she has dated mainly women and transmen, but isn’t opposed to dating cisgender men.

Just as important, she keenly feels that her gender is closer to that of her gay dad than to that of her moms. She and her dad, she says, are both “semi-boy-gender-fluid goddess-worshipping fairies” while her moms are androgynous dykes in the 1970s lesbian feminist mode. That makes her especially grateful to have him in her life, despite the years of alienation while she was in high school. Odd though it may sound to outsiders, her dad has been an important gender role model. “Gender matters and having role models matters,” she says, but your “same-gender” role model doesn’t have to be your same sex.

Lesson #8 They’re not allies. They’re family – literally.

But coming out as straight can also feel like being exiled from their native land. Dori Kavanagh, the therapist, says that it’s common for our offspring to feel unsteady in their identities once they start coming of age. “There’s almost the pressure to say that you’re queer-identified yourself,” says Kavanagh, “because you’re culturally queer.” No one wants to be called an “ally” when they are, quite literally, family. Some are outraged and offended that they’re cast out of the community and culture in which they were raised – including that feeling of being under siege together.

Says Annie Van Avery, “A majority of us feel deeply connected to our family roots as LGBTQ. I’ve spoken with many people who, if they are heterosexually identified as adults, mourn the loss of their queer families if they don’t feel connected day to day.” Annie herself grew up surrounded almost completely by gay people. First her father came out. Later, her sister came out. Finally, her mother the ex-nun took her aside and said: I’m worried about you – because I think you might be the only straight one in the family! For Annie, COLAGE was a lifesaver, a place where everyone understood how deeply she belonged.

They grew up with rainbows lining the bookshelves, with Pride as a happily awaited holiday, and their hearts cracked open with excitement hope the first time President Obama endorsed marriage equality. And so they’re beginning to insist that they fit, even if they are personally straight. Some call themselves “gaybies.” Others playfully embrace the term “queerspawn,” a word that insists that they were born amidst LGBT culture.

As parents we have to insist that our children belong amongst us. Confirms Annie, “especially in the last couple of years, youth in LGBTQ communities are being considered part of the movement. We are side to side with our parents, our support networks, with pride and affinity.”

Lesson #9: Teach them our cultural history.

Since the LGBT world is their home, help your children understand where our families fit into our national and international history. When it seems appropriate, show them the documentaries, movies, books, plays, posters – whatever feels most natural to you. Don’t shy away from the harder moments, whether those are Frank Kameny’s firing or the hatred during the AIDS years. They need to know you faced it down with dignity. They need to understand where they fit and what still needs to be done.

Understanding some of that helped Robin Marquis enormously. After she came out as queer and began hanging out more with her dad, he opened up and started talking about his activist youth as a Radical Faerie and queer writer. Hearing his stories of being one of the co-founders of Short Mountain Sanctuary in Tennessee and writing for the radical fairy magazine RFD made her feel she had a place in our history.

Lesson #10: Yes, of course, it is better now.

Of course, all the successes of the movement for gay and lesbian equality have made life easier for our children as well. Having parents who are free to marry and whose marriage must be recognized everywhere in the United States and Canada is enormously comforting. So is being able to see gay celebrities and families on television. All this makes your children’s lives more comprehensible to the people they meet.

And unlike when Robin, Annie, Dori, and Jenny were growing up, today the children of gay parents can tap into a large organized community, whether in person or online. “We are already there and supporting each other,” says Kavanagh, “so I think we are pretty darn lucky.”

Even better, society has progressed to the point that some people don’t even think there’s anything interesting about a gay family structure. “That was how I knew I wanted to go on a second date with my husband,” says Dori Kavanagh. She had started mentioning her gay mom on first dates as a screening device, to get rid of anyone who might be either uncomfortable or too excited. “When I told him he didn’t say anything. He was just, like, ‘okay.’ Like it was nothing. And I wanted it to be nothing.”

May that be true for your children as well.

SOME RESOURCES:

- A 2005 movie, Queerspawn. While some of the cultural context is dated, much else is accurate to how many children of gay families feel today.

- The Family Equality Council and COLAGE cohost Family Week.

- COLAGE programs, networks, and resources for and by people with LGBTQ parents, empowering each other to be skilled, self-confident, and just leaders in our communities.

- Abigail Garner’s 2005 book Families Like Mine

- Send us your resources to add to this list by leaving a comment or emailing Brian Rosenberg