Between the time we completed our first three-hour home study interview as a couple and our individual interviews with the social worker, we began to modify our home to meet foster certification requirements.

I’ll be honest – the very first time I heard that we would be required to “lock” any cabinets or drawers which contained medicine, knives, chemicals and/or alcohol, I had this vision of having gigantic, over-sized master locks securing all of our cabinets and wondered how in the world this environment could ever allow a child to feel comfortable in our home, much-less, part of our family. This isn’t an exaggeration – I seriously envisioned large silver and black dial-turning master locks securing our steak knives.

“Your Honor, please let this serve as evidence that never in my life had I ever imagined having children.”

Thankfully, a classmate asked if we were allowed to use Tot Loks, the infamous magnetic locking system that can be turned on and off, works wonders, but is a horrible, pain-in-the-ass to install. And so I ordered them – lots of them.

Wanting to ensure that no one would ever doubt our level of caution, I went Tot Lok-crazy and against Eric’s better judgment, I had them installed on nearly every cabinet in our home. From the laundry room to the kitchen to the wet bar, our home became one giant magnetic locking system. We were now officially prepared for either the worst natural disaster known to man or a child (or an invasion by wild orangutans who would be horribly frustrated by their inability to access our Benadryl or Drano or wine… or pretty much anything else in our house).

With our new first-aid kit fully loaded, our fire extinguishers on standby, our refrigerator lock box for medicine that must be kept cold tucked away nicely in the meat drawer and our bathroom lockbox for meds orangutan-proofed behind the Tot Locking system, we cruised through our individual interviews.

The series of questions in the one-on-one setting seemed more like an interrogation, which felt entirely appropriate at this point. The focus was now on discovering who we really we. What made us tick? Who made us hurt? What life-events turned us into the people we are today?

Going into this process I had thought that one of my biggest attributes was going to be that I had lost both of my parents by the time I was 32. I thought this would help me relate and understand and that this would be a valuable tool for me to help a child suffering loss. But what I found instead was that this experience was actually a concern.

The social worker asked me how I coped, how I grieved and if I was still grieving? “How did you deal with your loss,” she prodded. Would I reflect any issues I might still have about losing my parents on to my child? Ah, another one of those unexpected but perfectly clear reminders that this isn’t about you – it’s about the child.

Next came questions about Eric – a test of sorts. How well did I really know him? What was his family was like? His temperament? His emotional state? What drugs has he done? How much did he drink? What happens when …

Knowing that they would match my answers against his about himself, I began to worry that we might get some of these answers wrong. Was there something I didn’t know? Was there anything he forgot to tell me or that he needed to tell me but didn’t? After so many years together, did we really even know each other? What if the social worker saw something that we did’t?

Anxiety once again reared its ugly head. Were we really doing this? Was this the right thing? Or should we stop and just say it wasn’t for us? We expected that after a while this feeling of anxiousness would fade, but instead we reached the most unexpected point – the part where the hurt set in.

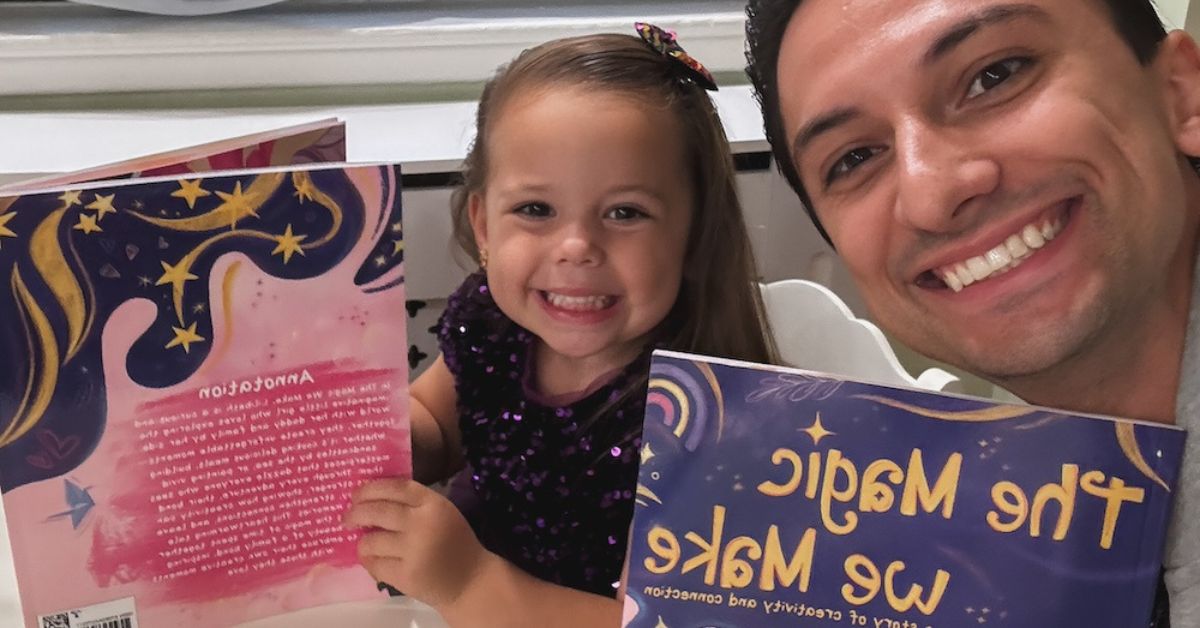

+ Photo credit: flickr, Rain0975, 20120127-IMG_2188