Dear birth mother,

Five years ago, on May 23, 2009, you went to Long Island College Hospital because you didn’t feel well. You were young, a single mother with an almost two-year-old daughter, living with your parents in Brooklyn. You knew you were pregnant, but you thought you had a couple more weeks before giving birth. It didn’t take long for a diagnosis: your water had broken two days before. A baby was delivered a half hour later. Apart from a little jaundice, for which he was briefly put on antibiotics, he was a healthy boy, even without any prenatal care.

Life was hard, so hard that you knew you couldn’t keep your newborn child. You knew this well before you gave birth, but you put off making alternative plans for the baby. You didn’t seek pre-natal care. Avoiding reality was a strong defense mechanism to avoid the pain.

So after giving birth, it was going to be foster care for your baby, until a doctor at the hospital suggested adoption.

Brian and I had been looking to adopt for a few years. A few months earlier, we had been in the process of adopting a six-month-old boy from upstate New York. We filled out all the paperwork. We met him, his mother and her boyfriend in person. There were some issues, the adoption agency told us, with the mother’s grandmother who wanted her to keep the baby, and the mother’s boyfriend who did not. After a while, the mother stopped communicating with the agency and with us, and we had no way to make contact with her. The adoption never took place. We never found out what happened to that boy. This pushed us to the front of the agency’s waiting line, just in time for the birth of your child.

As was customary, we made a brochure for expectant birth mothers to give them an idea of the life their boy or girl would get with us. It contained our personal story in carefully calibrated language, with attractive full-color photos of us, our relatives, our apartment, our neighborhood and our dog. Why we wanted kids. How much we understood the birth mother’s plight.

You asked the adoption agency if there was a family available to adopt him, a family like your own. Black, Baptist. There wasn’t. You said that a loving family was your top concern. You didn’t need to see any of the brochures, you’d trust the adoption agency to make the best decision. “A same-sex couple?” the agency asked. You said fine.

On May 26, the day after Memorial Day, we received the agency’s phone call about the little boy in need of adoptive parents. We were over the moon. And completely unprepared. For two days we were busy buying baby stuff, reorganizing our apartment, calling relatives and friends, planning his bris (Jewish circumcision ceremony), and searching for a last-minute baby nurse or doula to help us out the first few days.

Two days later, while we were getting ready to take a taxi to LICH, I came up with the first name of Levi: a beautiful Hebrew name that sounded like my dad’s, Leo. Brian had always liked the name Parlow, his beloved Nana Sid’s maiden name. And suddenly, the baby boy had a name, or rather, four names: Levi Parlow Rosenberg-Van Gameren.

We chose his first and his middle names, and we gave him our hyphenated last names. There was a linguistic version of the Heisenberg principle at work: as soon as we named him, we changed how we perceived him. We changed how we perceived ourselves. In an instant, we had become fathers. We named the boy after my father, after Brian’s maternal grandmother, and most important, after ourselves. The boy had magically become our son.

The agency’s instructions for the transfer were very clear: we should wait in the hospital lobby, in an Au Bon Pain, but we were not to go upstairs to the nursery. Further instructions: bring an outfit for the boy, a blanket, a hat, a car seat, and a camera. The picture our attorney shared with us provided us with a first glimpse: a tiny black boy with an oversized head, puffy eyes, and sleek black hair. We also received a photo taken of you, your mother and your adorable daughter while you were still in the hospital. (The family resemblance between siblings is striking.)

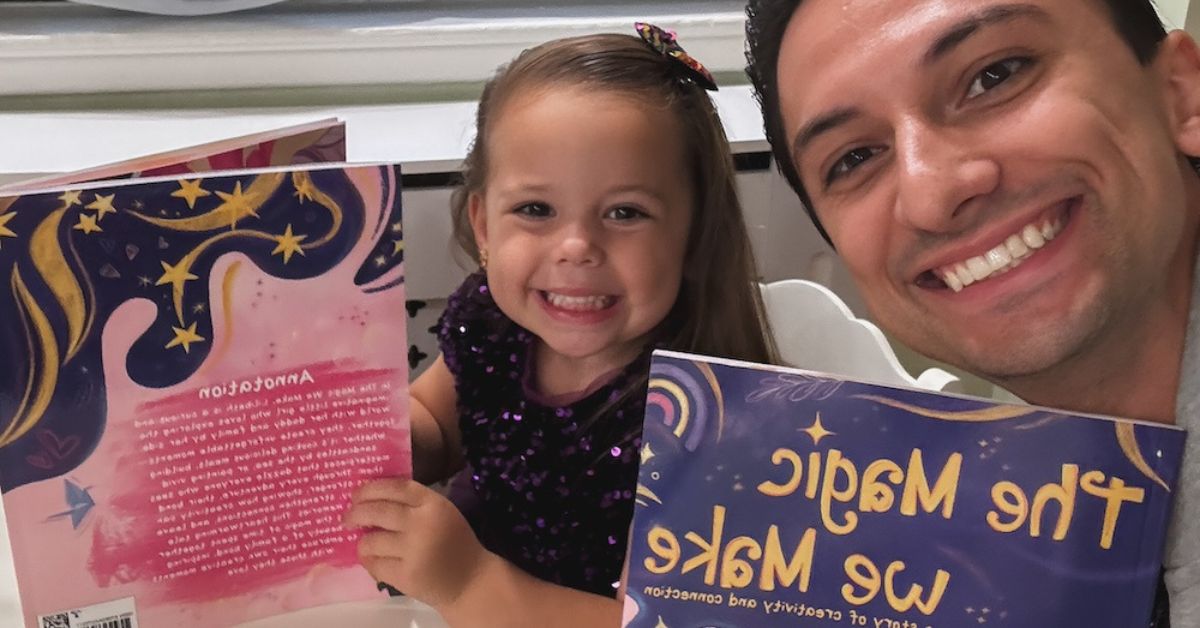

Levi knows he’s been adopted. For him that means that Papa and Daddy, who had been hoping for a boy for years, took him home from the hospital where he was born, to make a family. But sometime soon I expect that Levi will have more questions. He has already wondered why his sisters have white bodies while his is brown. He knows that a baby grows in a woman’s belly. When those questions come, we’ll answer them truthfully, in a manner he can understand, continuing the narrative we have already begun. We’ll also tell him that he has a biological sister. I hope that he will have the chance to meet you and your daughter one day. I imagine Brian and I will be there as well. I already know what I’ll say to him: “Levi, I’d like you to meet your birth mother.” And to you I’ll say, “I’d like you to meet Levi Parlow Rosenberg-Van Gameren, our son.”

Ours Truly,

Ferd

To help find your path to fatherhood through gay adoption, surrogacy or foster care check out the GWK Academy.