Editor’s note: This story was originally published in 2015.

It’s a scene that has played out so many times, it’s practically cliché: the surprise reunion of military parents and their children. Fresh from the plane, an Air Force dad surprises his daughter during her algebra class; an Army mom, dressed in fatigues, shows up unannounced to her son’s basketball game. Everyone cheers, choking back tears, as child and parent embrace for the first time in months.

Yes, it’s a tearjerker, but no matter your politics or stance on U.S. led wars, who doesn’t love to see parents safely reunited with their children? There is, however, one thing that bothers me about these reunions: I have never once seen this scene play out featuring an LGBTQ family as its stars.

“Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell” (DADT), the Clinton-era policy that banned LGBTQ people from serving openly in the military, is no longer to blame; the discriminatory policy was repealed in 2010, allowing stories about gay and lesbian service members to be covered in the media like never before. Last month, for example, a Navy man and his boyfriend were prominently featured in the media for becoming the first gay couple to share the ceremonial post-deployment “first kiss.” And social media was set aflutter last year when news broke out that gay and lesbian service members were allowed to perform in drag for a fundraiser on Kadena Air Base in Japan.

But stories featuring LGBTQ military parents and their children still manage to evade the spotlight. Their touching reunions aren’t televised, nor are the particular set of challenges they face often talked about. It was with this awareness that I reached out to Captain Chris Armijo, a gay dad with 17 years of experience in the Army, to discuss what life is like for him and his family in the post-DADT world.

* * *

“So,” I asked Chris, when we spoke by phone several weeks ago, “you’ve just recently moved your family from San Francisco to San Antonio, yeah?”

“Yes, that is correct,” Chris responded formally, making me immediately self-conscious for the clumsy “yeah” that had just escaped my civilian lips. But I shook it off and pressed on with the interview since amid his work, classes at Baylor University — where the Army had recently enrolled him to obtain a master’s in health administration — and raising twin 5-year-old daughters as a single dad, it was something of a small miracle that I’d managed to get Chris on the phone at all.

“Let’s see, I drop the kids off at pre-K at 7:40 in the morning, but then I need to be at my post at 8,” Chris said, after I asked him to describe a typical day. “The kids get done at 2:40, but the earliest I get out of my class is 3.” In his copious free time, Chris also volunteers at several organizations focused on LGBTQ service members and their families and helps run a playgroup for LGBTQ parents in San Antonio.

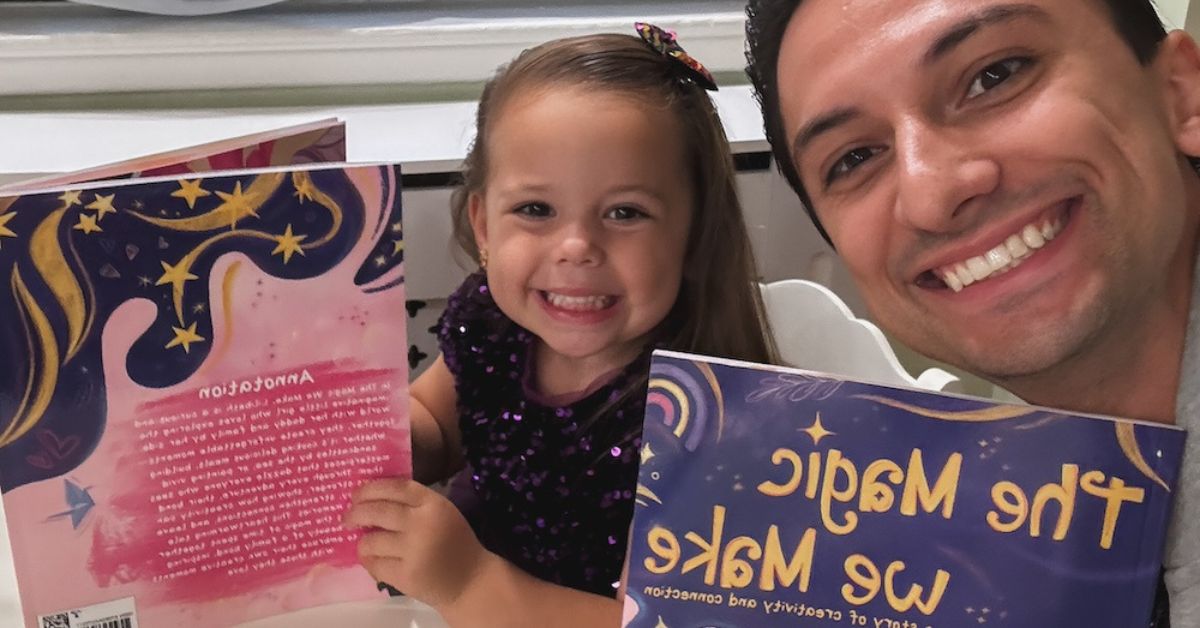

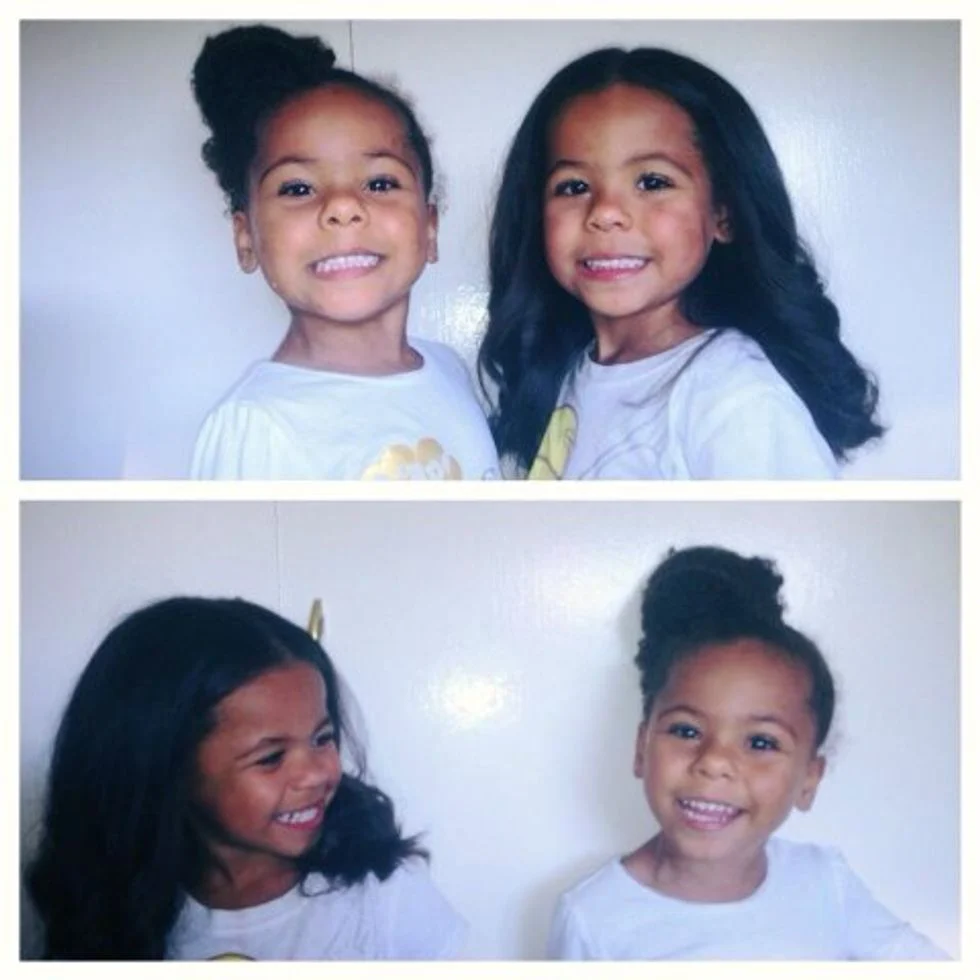

Keeping busy, moreover, seems to run in the Armijo blood. “I want the girls to try different activities so they can see what they may or may not have an interest in,” he said of his daughters, Sophia (in photo above, left) and Ryan (in photo above, right). “They’re doing a hip hop dance class with tumbling right now, a ballet class once a week, and a wrestling class.” He’d managed to squeeze our interview into the brief window of time he had between picking his daughters up from school and dropping them off at jujitsu.

I was exhausted just listening to Chris list off all his family’s obligations. But he shrugged it off when I asked if it all ever got to be overwhelming. “Sure,” he said, “there are some challenges to being a single military dad. But it’s the life I chose, and I wouldn’t change a thing.”

Volunteering as Tribute Gestational Carrier and Donor

“Anyway, I only have half an hour,” Chris said, getting down to business, “so where would you like to start?”

“Good question,” I thought. Where to start interviewing a gay Army man and single dad of twin daughters who recently moved to Texas by way of San Francisco?

“Umm,” I began nervously, weary of time, “I guess here: When did you first think about becoming a father?”

Chris has always known he’d have a family one day, he told me. He was simply waiting until the time was right, a moment that came over six years ago. “I’d just gotten to where educationally, professionally, and financially, I was in a good place to start a family,” Chris explained. “I’d worked my way up a career ladder in the military, and was ready.” That he was single and serving under DADT did nothing to deter him.

“The time just felt right,” Chris said simply.

Once Chris decided he was ready, the universe conspired to make his path to fatherhood a fairly seamless one. He had just began researching various surrogacy agencies (adoption, he mentioned, was out of the question under DADT given the extensive home visits and background checks that take place) when two women in his life, independent from one another, offered to lend their help.

“These are women that decided to go through this journey with me,” Chris said. “One volunteered to serve as surrogate and the other stepped up to serve as egg donor. That doesn’t happen everyday!”

Maybe it’s just the military backdrop, or maybe I’ve just seen too many fantasy movies, but there was something very Katniss Everdeen about the way Chris described these women — brave heroines altruistically “stepping up” to help someone in need — but I kept my nerdy “Hunger Games” comparison to myself, and instead asked how he knew these women.

Jessica, Chris’ egg donor, is a military friend who he’s known since they went through training together in 1999. His gestational carrier, Emily, is a more recent acquaintance, someone who Chris had known for a year and a half or so. Both women continue to play important roles in the lives of Chris’ daughters.

“They are known as ‘Momma Jessica’ and ‘Momma Emily,’” Chris said, adding that both friends make an effort to see the girls as much as possible. “And from the get-go, everything has been on the table,” Chris said of his arrangement with his friends. “[My daughters] know that they came from Momma Jessica, but that Momma Emily grew them in her belly.”

Hear No Gay, Speak No Gay

“It’s okay, we’re skipping jujitsu,” Chris told me, when I started panicking that our allotted half hour had somehow already slipped by. “I’m too tired,” he added, laughing. “Well, thank God for that,” I thought, “he’s human!” And I still had an almanac’s worth of questions for him: we hadn’t even began to talk about what life was like for Chris serving under “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell.”

“So, what was it like?” I asked gravely, bracing for what I was sure was going to be a difficult conversation.

“Oh, it was fine,” Chris said. I could almost hear him shrugging on the other end of the phone. “[DADT] didn’t really have much of an impact on me.”

Wait, what?

“I came out when I was 16 or 17 years old,” Chris explained, when I expressed my surprise. “I chose to be a soldier as a gay man. I joined knowing there was a policy in place that did not allow for me to be openly gay. That’s just what it was. It’s what I signed up for.”

Okay sure, Chris may have known what he was getting himself into. If you were going to join the military as a gay man under DADT, staying closeted was going to be a hazard of the trade. “But…” I said, my sense of social justice inflamed, “here you are gallantly serving your country but being forced to conceal part of your identity. Didn’t you feel discriminated against?”

“Not really,” Chris said, with another virtual shrug. “I may not have been able to talk about my plans for the weekend, or bring a date to a military function, but I still lived my life as a gay man under ‘Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell.’ We still went to gay clubs. I still dated.”

“But…” I pressed on, increasingly flummoxed, “weren’t you worried that you’d get caught and lose your job?”

“Oh, plenty of people knew,” Chris said. “They just never asked, and I never told. No one really cared. The people who knew didn’t care. Those who suspected didn’t care.”

“But…” I continued, finally at a loss, “wasn’t homophobia supposed to be just part of the military experience?” Weren’t anti-gay epithets just as integral to the armed forces as buzz cuts and barked commands to “drop and give me twenty?” Wasn’t any part of this difficult for Chris?

Here, finally, Chris took a moment before continuing: “What I can say is that I’ve heard just as much ignorance out of the military as I have in the military,” he said thoughtfully. “What I heard is nothing different than what I’d hear somewhere else. You hear the term ‘faggot’ in the mall or out on the street. I heard it in the military.”

I was stumped. This was so far out of the dominant narrative I was used to hearing about serving under DADT. I was used to stories told by people like Lieutenant Dan Choi, who was discharged under the policy for publicly coming out, on the Rachel Maddow Show, or retired Navy Captain Joan E. Darrah, who has written about the mental anguish caused by having to live two lives under the policy.

“You have to understand that my experiences are unique to me,” Chris said, explaining further. “My perspective comes from my own unique set of experiences, environment, and the people I worked with. My background was medical so I wasn’t in combat, arms or infantry. I know other people in the military have had very different experiences.”

While Chris may have been lucky in this regard, he also regrets that the public is less familiar with his type of story. “You never hear my perspective,” Chris said. “What you hear is the individuals who had negative experiences. That’s what people expect to hear.”

A More Visible Advocate

I had to admit it was actually quite nice to hear Chris’ version of what life was like serving under DADT. It was good to know that he, and hopefully others, were able to live their lives more or less openly, even under the discriminatory policy. But if DADT didn’t negatively affect Chris’ life much, was its repeal mostly a symbolic act for him? Did it have no practical import on his life?

“No it’s not just symbolic, that’s not at all what I’m saying,” Chris said. “[The repeal of DADT] has allowed me to become a vocal advocate for LGBT military families. I mean, you found me through a Google search, right?” Guilty as charged: I’d found Chris’ bio page on the website of the American Military Partners Association (AMPA), which advocates on behalf of LGBTQ military families. “I couldn’t have been that public about my work under DADT.”

Ryan and Sophia

Repeal of DADT has also had a profound impact on the lives of military partners and their families, Chris said. “A lot of gay individuals, their experience [under DADT] is where their partner has to be the ‘roommate,’ or the ‘nanny,’” Chris said. AMPA, he continued, was an important resource for these families, and was very active behind the scenes while DADT was still in effect. “These are individuals who had to carefully navigate the system,” Chris said of his work with the organization. “They had to live as second-class citizens in a system that did not recognize them.”

“How I got involved, I have no idea,” Chris said, laughing at the irony in his working for an organization that benefits military partners even though he is single. “I guess I take great selfies? I don’t know, but they let me into the club.” Chris was joking, however, because what he brings to the organization is clear. Chris’ primary role with the organization, for instance, is to help educate LGBTQ military couples interested in starting a family. As someone who has already navigated this process, he helps them do their research, and lay out their options.

Part of this work involves connecting service members with clinics that are not only LGBTQ-friendly, but welcoming of military personnel. “One of the things I’ve encountered [working with clinics] is that people’s conception of the armed forces is it being this draconic, homophobic, single group-think entity,” Chris said. “I try to break down those barriers, and link military personnel with military-friendly and understanding services.”

Though it came up almost as an afterthought, there is one other area where the repeal of DADT has had an impact on Chris’ life: It’s allowed him, for the first time, to consider having a long-term partner.

“Don’t get me wrong, I dated plenty,” Chris clarified. But the men Chris dated while DADT was still in effect “knew the deal,” he said. “They knew I was in the military, they knew it was ‘Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell,’ they knew we wouldn’t be the happy gay couple with me in uniform holding hands.” Given these limitations, Chris prioritized his career and his family over a partner. A relationship, Chris said, just wasn’t in the cards for him. Now that DADT has been repealed, though, “it’s opened up the possibility of having a career that I love and a partner or a husband.”

“Well,” I thought, satisfied, “there’s certainly nothing symbolic about that.”

“How Do I Clone Myself?”

As Chris listed off the various ways his life had changed as a result of DADT’s repeal, I was surprised to hear no mention of its impact on him as a gay father. Wasn’t it easier for him, as a gay dad, now that DADT has been repealed and he can live openly?

“I have to point this out all the time,” Chris said with a little laugh. “As a single guy, my sexual orientation had nothing to do with becoming a parent. People tend not to get this: had I been straight I would still have been single.”

Chris’ parenting challenges, he clarified, stemmed from being a single dad, not a gay military dad. “Ask any single parent,” Chris said, “we all struggle with the same thing: how do I clone myself? When my child is sick, what do I do? When I have to work late, who is going to pick up the kids? How do I buy my daughter a laptop computer to play on when I’m a single income parent?”

Far from being a source of his problems as a parent, in fact, the military has been a large part of his support system. “The leadership I’ve had since the girls were born has been phenomenal,” he said. “They accommodate whenever they can if I need time off, or if I need this or that.” The military has also worked to ensure that Chris, as a single parent, won’t have to uproot his family again anytime soon. After completing his Master’s degree at Baylor University in Waco, Texas, his career manager worked it out that Chris would stay in San Antonio, Texas for his residency and that he would do a follow-on assignment in San Antonio.

This isn’t to say that Chris has never faced challenges as a gay dad. These challenges just haven’t been as a result of the military. For example, when Chris first moved to San Antonio last summer, he enrolled his daughters in a daycare center. One day, his daughter Sophia came home crying. “Sophia had told her teacher that she had too mommies, Momma Jessica and Momma Emily,” Chris said of the incident. “But the teacher was like, ‘no we don’t have two mommies.’”

Chris, who had spent seven years in the Bay Area before moving to San Antonio, was taken aback. In San Francisco, “I was very much in a bubble,” he said. “It never dawned on me that I would need to have this conversation in a school setting. In San Francisco, so many of the families were gay or divorced or single parents. Our family structure was not unique. There were plenty of other families that looked like ours.”

To help make sure his daughters didn’t feel their family was different in San Antonio, Chris started a playgroup for LGBTQ families. “My thing is finding families that have structures similar to ours so when my daughters see two mommies or two daddies, it’s not out of the norm for them. It’s very important that my daughters don’t see our families out of the norm.”

“Dude, Seriously?”

As we finally ended our interview, I couldn’t thank Chris enough. Our call, scheduled for just 30 minutes, had stretched into over two hours. He had patiently and thoughtfully answered all of my questions about what life was like as a gay military dad, regardless of how intrusive, naïve, or civilian their nature.

Before we got off the phone, though, I had one last question: Are there any more kids in his future?

“Oh my God, dude, seriously? I’m so tired.” I laughed at this, a bit worried that I offended him, but mostly just happy that someone with 17 years of military experience felt comfortable enough by the end of our conversation to let a casual “dude” slip out.

And, as it turns out, my question wasn’t so far off base. “I am actually looking at the possibility of having a third child,” Chris said. “I am so exhausted most of the time. And I’ve accomplished a lot in my life that I’m proud of. But being a father, that’s my greatest accomplishment.” Also, he added, he may soon have more time to devote to parenthood. “I’m at that point where I’m looking forward to focusing on being a parent, not on a career. If I retire in four or five years, I’ll be able to go back to teaching part time if I want to. I won’t have to work a 40-hour work week.”

* * *

Before we ended our call, I asked Chris if there was anything else he wanted people to know about his life as a gay military dad. He left me with this.

“You talk about all the videos of returning soldiers walking into their kids’ kindergarten class to surprise them,” Chris said, bringing our conversation full circle, “and then you see an opposite-sex parent standing there crying. Do we have those? We do. Do you see them in the media? You don’t. But you need to remember that the military is an institution that just rewrote its history a couple years ago. We’ve always been there, but you’re just starting to see our families come out of the shadows. It’ll just take some time. Does that make sense?”

I was about to say, “Yeah, totally,” before I caught myself. “Yes,” I said instead. “That does seem correct.”